Dear Bird Folks,

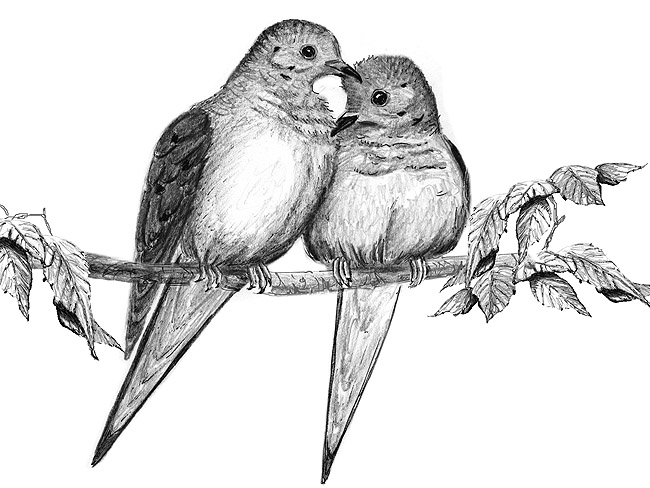

I’ve never been a big fan of Mourning Doves, but this summer I watched a pair in my backyard nuzzling (for want of a better word). Seeing doves doing a little nuzzling made me see them in a different light. I’ve heard you scoff at people who claim that birds can be in love, but how do you explain this nuzzling?

– Tracy, Hyannis, MA

Good, Tracy,

I’m glad you are seeing doves in a different light. I think they are underrated birds and are totally taken for granted. Folks become frustrated when they can’t attract birds such as orioles, bluebirds, hummingbirds or cardinals (especially cardinals), but Mourning Doves faithfully come to our yards everyday of the year and require no extra effort from us. I’m also glad you pointed out that your doves were nuzzling (for want of a better word). Most people wouldn’t notice or even care if they saw a dove couple interacting. Yet, the same people get all gooey inside when they see cardinals feeding each other, which is just plain gross if you ask me. Who wants food with cardinal spit on it?

With an estimated population of 350 million, Mourning Doves can be found in all fifty states, including Hawaii, where they have been introduced (much to the chagrin of the poor doves freezing here in New England all winter). Doves are extremely adaptable birds and are happy as long as they can find a few seeds to eat. They are also really good at breeding. (See? Nuzzling pays off.) A pair may produce four or more broods in a single year. And even though dove couples don’t remain together for life, they are faithful during the breeding season. BTW: The same cannot be said for other birds, including cardinals (especially cardinals), which have the habit of sneaking off for a “quickie” when their partners aren’t looking. Really. So, if the dove couples are faithful and can be seen nuzzling, they must be in love, right? No, of course not. Scientists call this nuzzling behavior you witnessed “allopreening.” Yes, allopreening. (Leave it to scientists to take the romance out of just about anything, even nuzzling.)

Allopreening is a poorly understood behavior that is performed by many birds. It typically involves a bird preening the head and neck area of its mate or even another bird in the flock. While this behavior might seem affectionate to us, in reality it is basically one bird helping to remove mites and parasites from another. How lovely. I’m not saying that parasite removal isn’t romantic…wait, no, that’s exactly what I’m saying. This behavior is more practical than passionate. Allopreening is performed by many bird species, including doves, crows, vultures and parrots. It is said that lovebirds, which are small parrots, acquired their name from their habit of frequent allopreening. I find it interesting that when the charming little parrots are seen preening each other, they are called “lovebirds.” But nobody thinks of love when crows or vultures preen each other. I smell a double standard here.

Keeping their feathers in shape is critical for birds. Their fragile feathers are the only things protecting them from the elements. During grooming they use their beaks to realign their feathers, remove dirt and add waterproofing. Birds are extremely agile and can reach most of their feathers, but even double-jointed birds can’t reach their own necks and heads. In order to groom these areas, some birds get assistance from their mates. And while this allopreening may not be a sign of affection, at least not by human standards, it does seem to help solidify the couple’s pair bond, and that’s important. Regular allopreening may explain why doves are faithful to each other (and aren’t like those trashy cardinals).

Speaking of preening, most birds preen with help from their oil gland, which is located at the base of the tail. Birds regularly spread oil over their skin and feathers. For years it was assumed that the oil made the feathers waterproof, like being coated with Scotchgard. But after further review, it turns out that the structure of the feathers is what makes them waterproof. The oil merely keeps the feathers from becoming brittle, like using hair conditioner. In other words, the oil is less like Scotchgard and more like Pantene…which is much cheaper.

By the way, none of this oil spreading applies to doves. This is because they don’t have active oil glands. Instead of oil, doves condition their feathers with something called “powder down.” Powder down basically is made of feathers that have disintegrated into a fine talc, kind of like talcum powder. The talc not only helps with waterproofing and feather maintenance, it makes doves smell better than just about any other bird, except for maybe the Cinnamon Teal, which reportedly smell like freshly backed apple pie. Get it?

I’m glad you have a new appreciation for Mourning Doves, Tracy. They might not be flashy, but they are always with us and that has to count for something. And while I don’t really believe there is a lot of love behind their habit of allopreening, I think it is way more romantic than getting a mouthful of cardinal spit. There is nothing hot about that.