Dear Bird Folks,

What kind of bird is this?

–Charlie, Orleans, MA

This one is easy, Charlie,

But before I answer it, I probably should inform the readers what we are talking about. Today, this guy, who turned out to be Charlie, walked up to me carrying a Baggie with a frozen bird inside. The bird had hit his window and, sadly, had died. But instead of burying the bird and then asking me about it, Charlie had the sense to put it in his freezer. This way, it would stay nice and fresh until he had a chance to bring it to me. (There are two things that I should point out here: One, keeping a songbird in your freezer is actually against the law, so if you do it, don’t talk (or tweet) about it or the NSA will find out. Two, a dead bird in the freezer is always an unhappy event, but it’s a fun way to freak out your houseguests.)

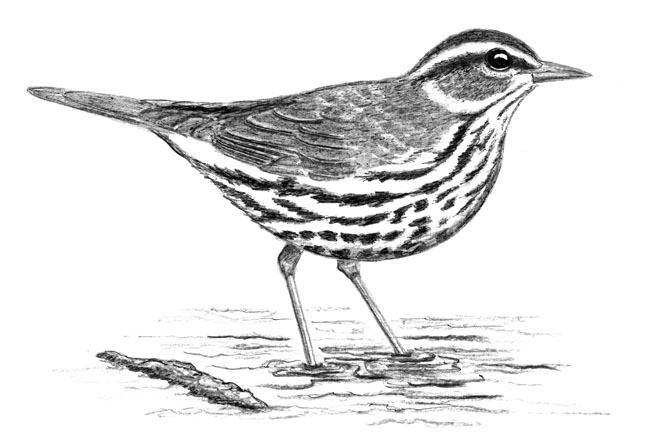

The frozen bird in the Baggie is (or was) a Northern Waterthrush. Ever hear of one before? No? It’s okay. Many people haven’t. They are basically transient birds that only stop on Cape Cod during migration. After I identified the baggie-bird, one of my workers tried to look it up in his bird book but couldn’t find it. The problem was, he looked under “thrushes.” In spite of their name, waterthrushes aren’t thrushes…and they aren’t made out of water either. Believe it or not, waterthrushes are actually warblers. You know warblers – those brightly colored birds that flit around the tops of trees. But the fact is, waterthrushes are nothing like their colorful cousins. They are brown, striped and dull, and actually look more like a real thrush than any warbler. Waterthrushes are colored to match their environment, which is wet bogs, dark swamps and other such areas that they share with spiders, frogs and anyone trying to avoid the NSA.

While Northern Waterthrushes aren’t easy to spot, they do have a few “giveaways” that alert us to their presence. They have a boisterous song that can to cut through the deepest woods, plus a loud, metallic chip call that they seem to use incessantly. But my favorite way to identify waterthrushes is how they walk. They can hardly take a single step without moving their entire backend up and down. It’s almost comical (and seems tiring) as the birds walk through the woods constantly bobbing their tail up and down. Watch a family of waterthrushes sometime and you’ll see as much bouncing booty as there is on Nauset Beach on a hot day in July.

Why does a waterthrush bob so much? (I’m pretending you actually care to know the answer.) Tail wagging is unusual, but it’s not unheard of. In fact, there are several species of birds in the Old World called “wagtails.” And Australia has its own tail-wagging bird called, “Willie Tail.” (How British is that?) But the Aussie bird doesn’t pump its tail up and down like the waterthrush. Instead, it has an even stranger habit of moving its tail from side-to-side, like a windshield wiper or doggy (tail) style. Some researchers believe all of this motion helps the birds find food. It is thought the constant motion flushes out yummy insects. Others think the continuous action prevents predator attacks. Huh? Isn’t it better for small birds to be inconspicuous? The theory here is that an active bird is more aware of its surroundings; thus predators will instead seek out a less attentive bird, like, say, the always-daydreaming Mourning Dove.

The best time to see waterthrushes is in May, when they stop on the Cape on their way to their breeding grounds, and later in August/September when they are heading back to the tropics for the winter. A few years ago a waterthrush visited my backyard. It poked around my little water garden, wagged its tail a few times before deciding my yard was too boring and headed out. This waterthrush was lucky. It was able to venture through my neighborhood without hitting any windows. Unfortunately, your bird, like too many other birds, had trouble with our walls of glass. Window strikes kill millions of birds each year and many of these birds die during fall migration. Young, newly fledged birds that have never experienced glass before likely have the most trouble with windows. What can be done to prevent window strikes? Funny you should ask.

Feeder birds often hit windows when they are startled by predators. If this is a problem in your yard, either move your feeders closer to your house (within three feet) so birds won’t have time to build up speed and thus aren’t badly hurt if they do hit a window. Or, move your feeders at least thirty feet away and that will give the birds more time to recognize your windows and hopefully avoid them. Migrating birds have a different problem than feeder birds have. They are often lost and confused. Closing your drapes and shades helps make your windows less dark and thus less mirror-like. Window decals also help, especially the new ultraviolet decals. Humans can barely see the decals but bird eyes can detect ultraviolet, which makes these decals more effective than the old-school black hawk silhouettes.

Sorry about your waterthrush, Charlie. Now that it’s been identified maybe you should bury it outside so it can continue on its journey in the circle of life. Either that or you could put it back in your freezer, which is my favorite thing to do. Legalities aside, I have several dead birds in my freezer and it’s been years since I’ve been bothered by any houseguests.