Dear Bird Folks,

I’ve enjoyed watching the Ospreys soar above my house all summer. Now that summer is winding down, I’ve been seeing them less frequently. I understand Ospreys migrate south for the winter, but where do they go, Florida?

– Donna, Centerville, MA

It’s interesting, Donna,

Ospreys are one of the Cape’s largest birds of prey. They are about 30% heavier than the mighty Red-tailed Hawk. They build massive stick nests and have far better fishing skills than any of those goofballs we see on the fishing channel. Yet, when it comes to dealing with winter they’re total wimps, no better than the human weenies who leave here when things get a bit chilly. The little chickadees, titmice and wrens face the winter with the rest of us, but Ospreys, and the other part-time Cape Codders, flee the second they feel the slightest nip in the air. What a bunch of babies. They miss our exciting Cape Cod winters.

You might be surprised to hear this, but you aren’t the only one who is interested in knowing where the Ospreys go each winter. Researchers have wondered about it so much that they have devised several ways to track them. The most common method is to pluck a baby from its nest and then snap a band, or two or three, on its legs. The little bird is then placed back into the nest and allowed to grow up in peace. After a few months of growing and figuring out how to catch fish, the young Osprey heads off, all by itself, to a place it has never been before. Many other migrating birds travel in flocks, but not Ospreys. They are strictly loners. Even the baby birds have to go it alone. So where do they go? I’ll give you a hint. It’s not Florida. It’s the place where Joe Kennedy gets his oil. Got it? Most of New England’s Ospreys spend the winter in Venezuela, and in other northern South American countries.

While this banding method can be productive, it’s not very efficient. It’s a lot of work to band a chick, not to mention dangerous. Have you seen how high some of those Osprey platforms are? I get dizzy looking at them. Yet some people, a lot braver than I am, somehow manage to climb up, avoid the angry parents and put leg bands on the bewildered chicks. And after all that scary work, they only have a slight chance of ever learning the fate of each bird that is banded. Many birds perish and are never found, while others are found by people who don’t have the interest or means to report a bird with a band on its leg. To improve their success rate, researchers have turned to technology. Today’s researchers simply punch up each Osprey’s Twitter account and learn exactly where the birds go and what they do every day of their lives. Okay, maybe they can’t do that just yet, but they have gone hi-tech.

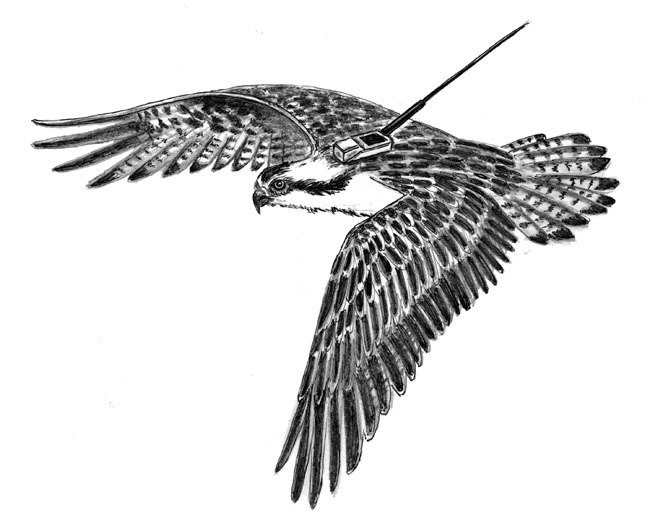

In addition to placing a band on a young Osprey’s leg, researchers now have the ability to affix a satellite transmitter to the bird. When I first heard about these transmitters I thought they were a bad idea. I mean, these poor birds have to fly thousands of miles. The last thing they need is a backpack filled with electronic gear strapped to them. But evidently all the added stuff doesn’t cause the bird any problems. Well, no problems except for peer ridicule. I’ve heard many of the birds with transmitters attached are teased about being tech nerds by their friends. (It seems the anti-bullying movement hasn’t found its way to Ospreys yet.)

With the help of the satellite transmitters scientists have been able to track an Osprey’s every movement. In addition, the transmitters provide other important information including flight speed, altitude and in some cases, the bird’s innermost thoughts. How are the transmitters attached, you ask? After the original method of nailing the transmitters to birds was deemed to be detrimental, a special harness was devised. Lightweight straps keep a transmitter, an antenna and solar-charged batteries safely on the bird for about three years. After that the entire package falls off. The timing couldn’t be better because three years old is when young Ospreys reach their breeding age and no bird wants to try to attract a mate while it has an antenna sticking out of it. Talk about awkward.

Here’s another good question to ask: is all of this work and expense worth the trouble? Yes, it seems it actually is worth it. Because of this tracking we now know where “our” Ospreys spend the winter (which I believe was your question). We also know that Ospreys migrate across the Caribbean, making them one of the few birds of prey not afraid to fly over water. We’ve also learned that Osprey couples mate for life. But they don’t really like each other very much, since they spend the entire non-breeding season totally separated. And once the babies leave the nest, they never knowingly see their parents or siblings again. (That last part doesn’t have much to do with your question, but I just felt like adding a little emotional drama.)

Some Ospreys spend the winter along the southern U.S. coast, Donna, but the bulk of them migrate to the tropics. In fact, there are websites where you can track an Osprey’s daily movements. You should track one sometime. I do. It gives me something to do after the summer ends. See, I told you Cape Cod winters were exciting.