The Amur Falcon,

I’d bet few people reading this have ever heard of an Amur Falcon, and until last night I hadn’t heard of it either. I was going through my mail, sorting the bills and traffic citations from the letters saying, “ You may have already won,” when I opened a flyer from the Essex County Ornithological Club. The club was sponsoring a talk by famed writer/researcher, Scott Weidensaul. (Scott’s last name is pronounced, “Why-densaul,” but from now on, we’ll just call him “Scott”). The lecture was to be held at Salem’s Peabody Essex Museum (that wonderful place that was built in between witch trials). I immediately became fascinated by the Amur Falcon story and was making plans to attend the lecture, when I noticed that the date of the talk had already come and gone. The flyer was sent out a week late and I had missed the lecture. (I think the club needs to spend some of its dues money on a new calendar.) I was still interested in the falcon story, so I watched the lecture online, and was really glad I did.

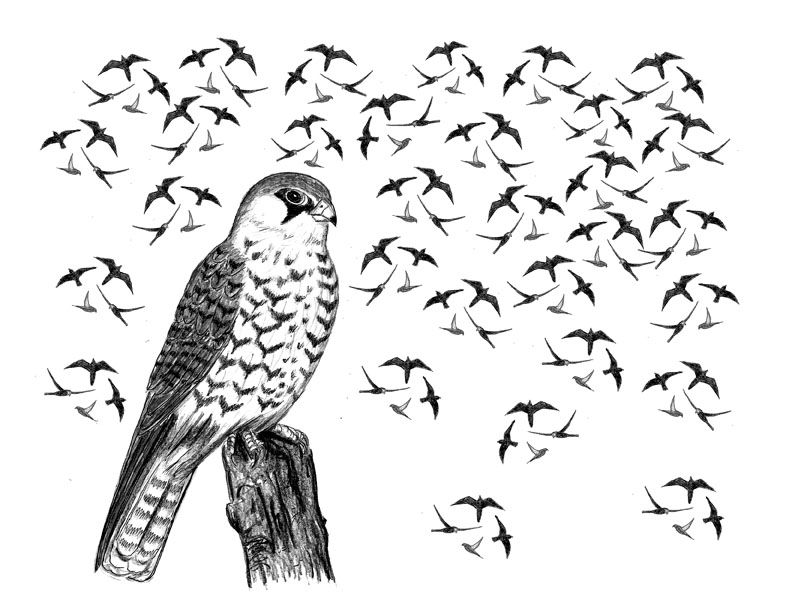

Slightly larger than an American Kestrel, the beautiful Amur Falcon breeds in parts of China and Russia, and each fall makes a 9,000-mile migration to Southern Africa. Much of this migration is done without stopping, other than one important refueling stop in Nagaland. Nagaland sounds like the latest addition to a Disney theme park, but it’s actually an isolated area of Northeast India. Due to its remoteness, inaccessibility and local unrest (headhunting existed until 1969 and guerrilla fighting with bordering Myanmar continues still), the “outside world” didn’t know about this avian spectacle. And by the time we found out, it was almost too late.

Each fall, on their journey south, Amur Falcons stop here to rest and feed on, of all things, hatching termites. We think of falcons as fast predators, chasing and capturing other birds on the wing, but Amur Falcons don’t need such drama in their lives; they would rather focus on bugs. From late October until mid-November, after the monsoon rains pass, between one and three million (yes, million) falcons descend on Nagaland. The birds spend their days eating flying termites, and at night they sleep in massive roosts. The bulk of the birds’ activity is concentrated around a dam and a reservoir that the Indian government built in the year 2000. The dam’s hydro plant provides electricity for the region, which is good, but the reservoir also flooded the area’s farmland, which is bad. As a result, the poor farmers became even poorer. Some of them tried fishing in the reservoir, but were only minimally successful. Their next step was more dramatic. The fishermen took their nets out of the water and hung them in the trees in an effort to catch…you guessed it, falcons. Instead of fish, nearly two hundred thousand (yes, two hundred thousand) migrating Amur Falcons were being caught and sold in nearby markets for meat. An avian spectacle was quickly becoming an avian catastrophe. Then something almost beyond belief happened.

When word of the falcon slaughter finally reached the rest of the world, the outrage was loud and direct. Environmentalists converged on the area in order to convince the inhabitants that the falcon killing had to stop. To which the local people replied (and I’m paraphrasing): “Oh, okay. We won’t do it anymore.” And that was the end of that. The nets came down and the falcons were never harmed again. This instant reversal of behavior seems almost too good to be true, but once the Nagas realized that what they were doing had long-term environmental consequences, they stopped. This amazes me. In an age where “developed” countries won’t stop whaling, clear-cutting or burning coal, the villagers of Nagaland totally got it. High-five, Nagaland.

This brings us back to Scott and his lecture (that I missed). I don’t know how many folks are familiar with Scott’s work, but just reading his résumé makes me tired. He’s written over two dozen books, was nominated for a Pulitzer and has studied and banded birds (particularly owls) all over the world. When he heard about the falcon concentration in Nagaland, he immediately began planning a trip. Scott not only wanted to experience the falcon show firsthand, but he also sought to support Nagaland’s fledgling eco-tourism industry. By preserving the falcons, the local people had done the right thing, but now they need to find a new way to earn a living. It was hoped that tourists, especially birders, would provide the villagers with much needed revenue, but so far things have been slow to develop. Hmm.

One of the biggest obstacles with bringing tours in to see the falcons is access. Even the main road into the area is muddy, rough and scary (kind of like driving on the roads in Orleans Center). In addition, the accommodations are pretty basic. While the people are friendly (no more headhunting) and they all speak English, for some reason they don’t use mattresses, even in the guesthouses. There is no padding on the beds whatsoever, just wooden planks. In Nagaland, you literally get room and “board.”

Anyone interested in learning more about this amazing story should check out A Galaxy Of Falcons online, or the video, The Race to Save the Amur Falcons. Some of the scenes are tough to watch, but just keep in mind there is a happy ending. Also, if you are up for an adventure, Scott has put together another trip to visit the falcons this fall (2019) and is looking for people to join him. I was going to sign up, but I’m still recovering from driving on the roads in Orleans Center.