Dear Bird Folks,

Why don’t birds use birdhouses in the winter? Wouldn’t birds be warmer in a box than out in the open? BTW: After my baby birds fledged this summer, I cleaned out the boxes…just like I’m supposed to do.

– Sharon, Brewster, MA

You’re a good kid, Sharon,

As with birdfeeders and birdbaths, it’s important to regularly clean out our birdhouses. Last spring’s beautifully crafted nest quickly begins to decompose and attract all kinds of creepy things. I’ve already cleaned out my boxes, too. My wife says I devote more time to my birdhouses than I spend cleaning our own house. I respond to her allegation by saying that if she weren’t such a slob maybe our house wouldn’t need to be cleaned as often. (At least that’s what I say in my head. In reality, I just nod. Nodding is always the safer alternative.)

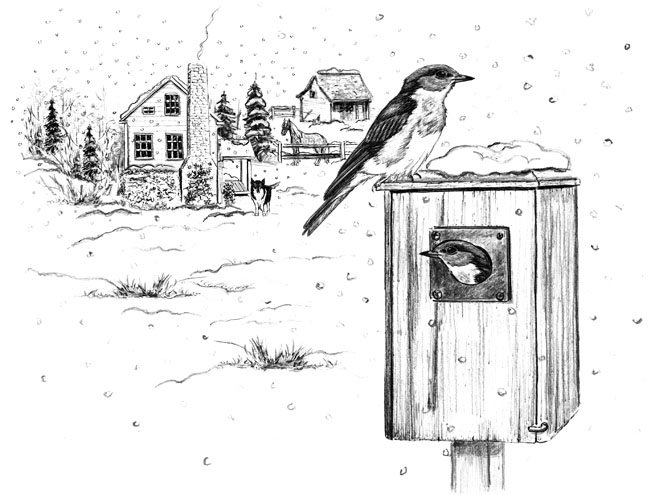

It really is surprising that more birds don’t use birdhouses when it’s cold out. If I were a bird, I’d much rather spend a cold night curled up in a birdhouse than desperately clinging to a windswept tree branch. In fact, studies have shown that when a bird does sleep in a cavity, the ambient temperature rises by a few degrees. Raising the temperature by only a “few” degrees may not seem like much when it’s, say 10° outside, but for a tiny bird a few degrees could be the difference between surviving the night and not waking up at all.

Yet, few birds choose the cozier option. Goldfinches, for example, could easily fit into a birdhouse, but no matter how nasty it is outside, they won’t go inside. They prefer to gather in thick cedar trees, using the trees’ trunks to break the wind. Larger birds, such as gulls, even take things a step further: they don’t even use trees for shelter. They sleep out on the beach (or some similar location), totally exposed, with nothing to block the frigid wind, except other gulls. Brrrr.

It’s hard to say why more birds don’t sleep in birdhouses. Maybe they have unresolved issues with claustrophobia. Still, there are a few that don’t mind being in confined spaces and they tend to be the same birds that nest in birdhouses. One bird that likes to sleep inside is my buddy, the Black-capped Chickadee. Just don’t expect to find a chickadee in a regular birdhouse. Typically, they use smaller, more natural cavities. I’ll explain.

During the day, chickadees travel in loose flocks. But by the time nightfall rolls around they are pretty sick of each other, so each bird tends to find its own place to sleep. Sometimes these roosting locations are in dense thickets, but often, especially when it’s cold, tree cavities are used. Because they like to sleep alone and don’t have a partner to help keep them warm (or to steal the blankets from) chickadees look for small cavities. The smaller the space, the warmer the birds stay. Due to their desire for cramped spaces, chickadees aren’t as likely to sleep in a spacious birdhouse. But not all birds subscribe to this solo sleeping philosophy. Eastern Bluebirds know that there is safety in numbers and there is also extra heat, so they often bed down together in one big pile…just like hippies from the sixties. (Ah, the good old days.)

In the spring, bluebirds readily raise their families in birdhouses, but these same birdhouses will also help keep the birds alive in the winter. And when it comes to keeping warm, bluebirds subscribe to the “more the merrier” philosophy. Over a dozen individual bluebirds have been observed moving into a birdhouse on a cold night. The highly organized birds gather on the bottom of the box, forming a tight circle, with their tails in the middle and heads facing out. Famed bluebird photographer, Mike Smith (no relation), took a ridiculously cute photo of one of these roosts. The photo shows eleven sweet-faced bluebirds, huddling shoulder-to-shoulder in a circle, each one staring up at the camera. Some companies make specially designed winter roost boxes that contain several perches for the birds to sleep on. But because bluebirds tend to gather on the floor (like hippies), they aren’t inclined to use these boxes. (Keep that last part quiet because we sell lots of those roost boxes.)

One bird that takes a more traditional approach to roosting is the lowly Carolina Wren. Like newlyweds, this wren often spends winter nights cuddling up with its mate. Wrens sometimes use birdhouses, but more often they slip into something much smaller, including specially-made roosting baskets. We have one of these baskets under our porch and when I look out at night I usually see two tiny wren tails poking out of the entrance hole. Aw! (Even a curmudgeon like me thinks it’s sweet.)

Most birds have to search to find a roosting site, but not woodpeckers. They can create all the holes they need. Throughout the fall, Downy Woodpeckers dig out an assortment of cavities. Having more than one cavity gives the birds options in case one of their holes is lost in a storm or taken over by a squirrel. (Humans aren’t the only ones with squirrel issues.)

I’m glad you’ve already cleaned out your birdhouse, Sharon. Maybe you’ll get lucky and have a pile of bluebirds move in. I’d write more about this topic but I think I should do a little housework before my wife gets home and reads this column, or I could be sleeping with the gulls tonight. Brrrr.