Dear Bird Folks,

We’ve had Chipping Sparrows in our yard all summer. Why haven’t you ever written anything about them?

– Brian, Falmouth, MA

Here’s why, Brian,

I haven’t written about Chipping Sparrows because no one has asked about them, that’s why. Gee, that was easy. I wish all of the questions I receive were that simple. Okay, fine; here’s more sparrow info.

With an estimated population of 230 million, Chipping Sparrows are one of the most common birds in North America, or the world for that matter. Yet most casual birders don’t know (or ask) anything about them. Why is that? It’s because they’re sparrows, that’s why. Backyard bird watchers are too focused on hummingbirds, orioles, cardinals and the other “pretty” birds to spend time sorting out the dull ones. This is too bad because Chipping Sparrows are distinctive and charming. I know it’s hard to imagine a distinctive and charming sparrow, but in this case it’s true…mostly.

To begin with, chippers get their name from their “chip” call. No surprise there. They are tiny birds, weighing about half as much as a Song Sparrow and are thinner than a goldfinch. Their slightlyness (?) is especially noticeable when compared to other feeder birds. Chippers are black/brown on the back and light gray on the belly, which are pretty standard colors for a sparrow. It is the birds’ head pattern, however, that makes them stand out. During the breeding season, chippers have a distinct black line running through each eye, white eyebrows and a bright rusty cap on their heads. This might not sound very exciting, but it’s enough to get our attention. Every spring, my wife calls me over because she thinks she sees a “new bird.” I tell her it’s a Chipping Sparrow and she gets it…until the following spring, when she again calls me over to see another new bird (another chipper). It’s an annual ritual… even though she doesn’t realize it.

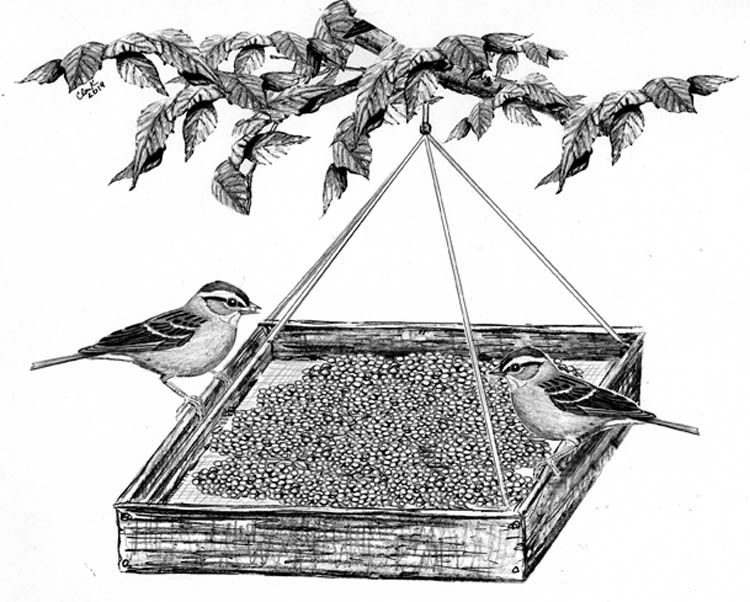

Because of their petite size, chippers are easily displaced at feeders by larger birds. While Chipping Sparrows may be intimated by other birds, they don’t seem to mind people. I’m not saying that they actually like us (as catbirds appear to), but they don’t seem to dislike us either. We are basically neutral to them. The other morning I was putting out my feeder* and before I could even place it on the hook, a chipper landed on it and started eating. Being the softy that I am, I stood there for a few minutes, still holding the feeder, while the little bird ate. Eventually, though, I had to put the feeder on its hook, as my arm was getting tired, but more importantly, breakfast was ready.

*I put my feeder out each morning because I take it in each night. If I don’t, the raccoons will have their way with it. I’m mentioning this because too many people still blame squirrels whenever their feeders have been knocked down or have disappeared. Yes, squirrels are eaters and chewers, but they’re not knockers and stealers. If your feeders are getting whacked, try taking them in at night. Also, stop blaming the squirrels for everything that is wrong in the world. There are a few problems that aren’t their fault.

Last spring, when everyone seemed to be getting Indigo Buntings, I put out a feeder filled with white millet. I’ve never been a fan of millet, but buntings actually like it, so I gave it a shot. It didn’t work. No buntings ever darkened my feeder, but the chippers loved it. My tray feeder often appeared to be empty, until I looked more closely and saw a rusty capped little chipper picking away on it. Because of the Chipping Sparrow activity, I kept the millet feeder filled, long after the bunting craze had waned. Since then I have discovered that a surprising number of other birds also eat white millet, including cardinals, doves, and Blue Jays. Grackles and squirrels will also occasionally try millet, but they don’t seem happy about it.

Chipping Sparrows may be shy around other birds, and tolerate people, but they aren’t bashful with each other. In fact, they are a little bit on the trampy side. A study in Canada suggests that after a chipper couple has set up a territory, the male will travel to other territories and visit other females, where the two birds will…well, you know. This likely explains why the Chipping Sparrow population is so high. Actually, the reason why we have so many chippers is in part due to the birds’ ability to take advantage of the changes we have made to the landscape. Parks, fields, orchards or anyplace where there are weeds and unkempt grasses is appealing to them. One of my favorite places to find Chipping Sparrows is in the nearby public cemetery. Sometimes there are so many chippers in the cemetery they actually outnumber the dead people (although the birds tend to be more active).

I should mention, Brian, that soon these distinct birds won’t be so distinctive. After the breeding season, the bright rusty cap and white eyebrows become duller. In other words, soon Chipping Sparrows will look more like the other confusing sparrows. In the fall, they’ll join a flock and begin their migration to the Southern states for the winter. A few chippers spend the winter on the Cape, but most won’t be back until spring. And when they return, they’ll be wearing their stately breeding plumage once again. At my house I always know when the chippers have returned because my wife will call me over and say, “I think we have a new bird.” The ritual continues.