Dear Bird Folks,

We like to watch the ducks in the local ponds, but due to the recent cold snap, all of those ponds are frozen solid. What has happened to our ducks? Where do they go?

– Callie and Al, Eastham, CT.

Let me explain, Callie and Al,

Before I get to your missing ducks, I need to make it clear to everyone else that there is no such place as “Eastham, CT.” Callie and Al are two young siblings who came to me with a question about ducks. But they made the mistake of also coming in with their parents, thus anytime I asked a question, everyone (mostly the adults) answered all at the same time. Through the confusion I heard someone say something about being from Eastham or Connecticut, or both. And, just to add to the chaos, the kids introduced themselves as “Callie and Al,” while their parents called them completely different names. By the end of the conversation, I was totally confused and have no idea where Callie and Al are from, or what their real names are. Although, I’m 100% positive they asked about ducks…I think.

Like many coastal communities, Cape Cod has always been a good place for birders to look for ducks. Our lakes, secluded kettle ponds, marshes, estuaries and assorted bays are the habitats ducks seek. And Orleans is so duck-friendly, we even have a street with the lovely name of “Old Duck Hole Road.” (That’s pretty good for stodgy old Orleans.) For the most part, the best time to see ducks on the Cape is in the winter. Why is that, you ask? It’s so busy here in the summer that even the secluded kettle ponds are overrun with activities, and the ducks know it. They would rather raise their families farther north or in the quiet isolation of the prairie states. But those areas are far less hospitable when winter arrives, so the majority of them head south, or to the coast, or in some cases, to Cape Cod, where things are far more temperate…or at least they’re supposed to be.

For years I’ve preached that length of day and moving cold fronts are the triggers for bird migration, and not necessarily food availability. That is why our feeders don’t prevent Ruby-throated Hummingbirds from leaving here each fall. This is not totally the case for waterfowl, however. The amount of daylight is an important cue, but many ducks don’t do any serious moving until they are forced to by the weather. For example, the Cape Cod Bird Club conducts an annual waterfowl survey. Each fall, diligent birders spread across the Cape and count every duck they find (even the ones on Old Duck Hole Road). When it first started, the count was held in early November, but due to climate change (you know, that phony phenomenon), there were no ducks to count. So, the survey was moved to December, when cold weather in the north finally forced ducks our way.

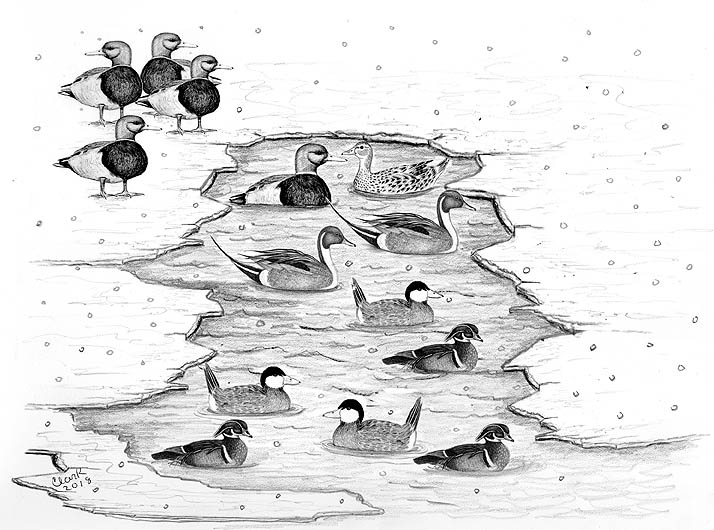

One of my favorite spots to see ducks is Herring Pond in Eastham (Eastham, MA not CT). This is a reliable place to see Ring-necked and Ruddy Ducks, and American Coots, which really aren’t ducks, but are close enough. Sometimes this little pond remains open and active all winter; other years, it freezes solid. When that happens the ducks may move around the corner to the larger Great Pond. When that pond becomes iced, the ducks are forced to move again. They may fly to nearby Town Cove, or Nauset Marsh, or Pleasant Bay or to some other hidden place they haven’t told me about.

Around here, open water is never hard to find. After all, we have the Atlantic Ocean and that never freezes, right? Yes, at this latitude the Atlantic doesn’t freeze (although it might this year), but not all bodies of water are equal. The open ocean is fine for deep-diving ducks such as eiders, scoters, mergansers and even Buffleheads. But what about the dabblers, those freshwater ducks that feed by tipping their bums up in the air? Mallards, teal, widgeons and pintails can’t find food in the rolling surf. They need shallow water to forage in. Tidal marshes and river estuaries are their plan B when freshwater ponds are no longer available. Speaking of freshwater, how is a freshwater duck able to survive in a saltwater environment? Doesn’t drinking saltwater make them sick? No, not really. They have a plan B for that as well. Ducks have built-in salt (removal) glands, which enable them to drink or at least ingest some seawater with no ill effects. Unfortunately, humans don’t have salt glands. But if we did, I would spend half of my grocery money in the chip and pretzel aisle.

Ducks are highly mobile creatures. If they become iced-out of one location, they simply move to the next one. Last week, Casey visited the now famous West Dennis Beach. While everyone else was looking for the Snowy Owl, he was busy photographing a surprising number of ducks that had discovered a bit of open water near the bridge. Between the tides and our estuaries, ducks can usually find a place to go. And if not, they are quite capable of flying to Nantucket, Long Island or even to Chesapeake Bay. Although, the way this winter is going, the closest ice-free location may be Tijuana.

No matter how cold it gets, Callie and Al (or whatever your real names are), eventually things will warm up and the ducks will return your ponds. If you have any more bird questions, please feel free to stop in again…but leave your parents in the car. (Just kidding. Bring them in. They are really good shoppers.)