Dear Bird Folks,

I understand birds have territorial conflicts in the spring, but the turkeys in my yard have been squabbling since the fall. I enjoy seeing them, but why so much aggression in the non-breeding season?

– Marilyn, Orleans, MA

Good for you, Marilyn,

I’m glad you are enjoying your turkeys. The return of Wild Turkeys to much of their former range is an environmental success story, but not everyone is excited about it. For example, people with trophy lawns aren’t always happy when a flock (actually called a “rafter”) of turkeys ignore their “keep off the grass” signs. They say the birds are messy. I can understand why some folks aren’t turkey fans, but I don’t understand why they complain to me about it. I’m not the turkey police. Grumbling to me about turkeys, or any other bird, is like going into Starbucks and complaining about coffee. You aren’t going to get a lot of sympathy.

For most birds, spring is the season of conflict. This is when they claim their breeding territories. But with turkeys, squabbles can break out anytime of year. They are always ready to drop their gloves and mix it up at a moment’s notice. The entire flock could be getting along just fine, then one bird wakes up on the wrong side of the nest, becomes a little too aggressive and suddenly things turn ugly. Why fight in the fall? It’s the ol’ pecking order thing. And turkeys aren’t the only ones. A flock of chickadees (called a “banditry”) is not as sweet as it seems. It might not be obvious to us, but within each flock there’s a dominant chickadee, which is the reason why the other chicks take one seed from a feeder and fly away. They aren’t doing it to be polite; they’re afraid of the evil top-chick.

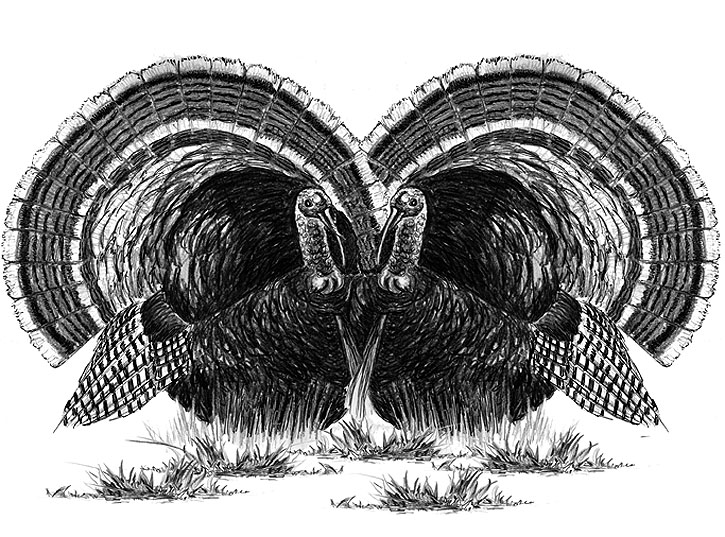

Typically, the dominant bird is a male (sorry, ladies), but it’s a little different with turkeys. Turkeys travel in segregated groups. The older males live in one rafter, the young males live in another and females of all ages gather in yet another. You might assume that within a flock of males there will be habitual battles to be the top-turkey, and you would be correct. However, things are just as contentious over in lady land. They too have their share of conflicts and it is not a pretty sight. When the hens fight, there’s a lot of kicking, scratching and biting. (Don’t laugh, fellers; the macho toms fight the same way.) The goal for each bird is to grab the other combatant by its beak, neck or snood. (FYI: The snood is that weird fleshy piece hanging down from a turkey’s forehead. It looks pretty gross, but during the mating season the females choose the male with the longest snood. You can draw your own conclusion of what that’s about.)

The battle may continue for a while, but it usually ends when one of the birds gets a firm grip on the other and forces its head to the ground. Once pinned, the loser bird has to either tap out, say uncle or wiggle free. Occasionally, there’s a brief pursuit by the victor, but more often than not the birds simply calm down and go about their business. The loser bird isn’t ostracized from the flock or forced to buy lunch for the winner, but from that point on all of the other turkeys know who the boss is…at least until the next fight breaks out. It should be noted that both sexes engage in such battles, but the females do it less often. (They know how silly it all looks.)

The scuffles in the off-season are to establish a hierarchy within the flock, but in the spring the fights are all about breeding. As the weather improves and the days become longer, the males begin to gobble and strut their stuff in an effort to attract hens. While the dominant male has the greatest chance to breed, the subordinate birds may also hook up, but only if the alpha bird isn’t looking. Even though the males think they’re hot stuff, ultimately it is the female who chooses her mate. She looks over the field of suitors and chooses the one she likes best (you know, the one with the longest snood). After mating the female will head off, find a hidden area on the ground, construct a nest and lay a dozen or so eggs. Meanwhile, the male keeps gobbling and strutting, in hopes of getting lucky again, and again. When it comes to breeding, he only has one job to do and it doesn’t last very long. Such are the advantages of having a long snood.

After hearing about your turkeys, I decided to drive through your neighborhood to check out the rafter. Casey and I arrived after work, just as it was getting dark. The birds had finished foraging for the day and were getting ready for bed. Turkeys spend their days on the ground, but at night they move up into the trees for safety. If you think turkeys look goofy on the ground, you should see them try to fly. It’s a common misconception that Wild Turkeys are stupid, but these fat things sure looked ridiculous as they ran and flapped to takeoff. After a short flight, a bird would crash land into a tree, breaking branches and barely hanging on to limbs. Each one looked as if this was the first time it had ever used its wings. If the turkey police were around, these birds would certainly have been stopped for OUI or more accurately, FUI.

Turkeys are fascinating birds, Marilyn. They may squabble a bit and can be a little messy, but if you think about Thanksgiving, you’ll realize how important these birds are to us. They are an essential part of America’s culture, and are certainly more essential than some other things, such as trophy lawns.