Dear Bird Folks,

Last week I saw a flock of eighteen (yes, eighteen, I counted them three times) turkeys walking along Station Ave (in Yarmouth, MA), right across from the high school. All eighteen were exactly the same size, shape and color. Do you think they were all a family? Could one mother have hatched all eighteen eggs? Why wasn’t there a runt?

– Peggy, Cambridge, MA

They’re probably freshmen, Peggy,

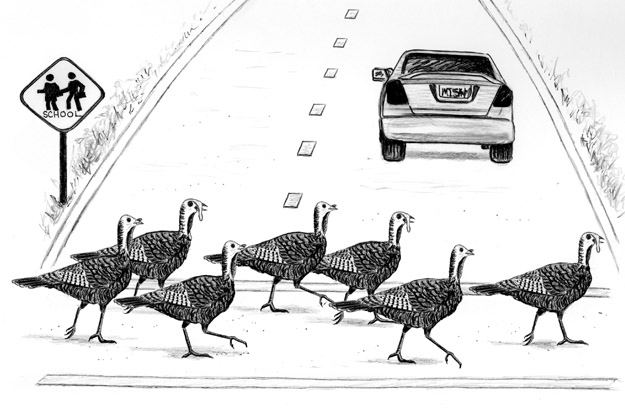

The turkeys you saw near the high school were probably members of this year’s freshman class, the class of 2015. Yarmouth has one of the Cape’s most progressive school systems. They won’t deny a proper education to anyone, turkeys included, as long as he or she makes the appropriate commitment. As a result, Cape Cod has some of the best-educated turkeys in the country. Many of the Cape’s turkeys have gone on to study at major universities and have become important members of the community, where they continue to work to abolish Thanksgiving.

It wasn’t very long ago when the idea of seeing a Wild Turkey on Cape Cod was unheard of. The Checklist of the Birds of Cape Cod, produced in 1985, doesn’t even list them as being here. For years the State tried to reintroduce turkeys to western Massachusetts, but with little success. They kept stocking the woods with stupid turkeys from game farms and it wasn’t working. Game farm birds were accustomed to having breakfast in bed each day and lacked the skills needed to survive on their own. Then, in the mid-70s, wild Wild Turkeys, borrowed from upstate New York were released and that did the trick. The wild birds quickly began repopulating the western part of the state. None of this helped Cape Cod, however. Everytime the birds tried to migrate to the Cape, the Army Corps of Engineers had once again reduced bridge traffic to one lane and the back-up scared them away. Then in 1995, a few dozen descendants of those transplanted New York wild Wild Turkeys were released in Wellfleet. (Swell, that’s all the Cape needs, more transplanted New Yorkers.) Once again the program worked and the local turkey population has been growing ever since.

The male turkey is known for his showy breeding season displays. He struts around, puffs out his chest, fans out his magnificent tail and gobbles his head off. While there is no denying that the male puts on a good show, he does little else to help produce more turkeys. The female is the one that builds the nest, lays the eggs, incubates the eggs and raises the kids. On average she’ll lay a clutch of a dozen eggs, or a baker’s dozen if she’s feeling generous. While twelve is the average, it’s not unheard of for a female to lay seventeen or eighteen eggs at a time. This could have been the case with the eighteen turkeys you saw last week. There’s a slight chance that they were all from the same family, but it’s unlikely. While the hen is good at laying lots of eggs, the single mama often struggles to protect her newly hatched chicks from hungry predators. I know it seems strange, but there are creatures out there that actually eat turkeys. Can you imagine?

Only about thirty-eight percent of the baby turkeys survive longer than two weeks after hatching. That means if a hen really does lay eighteen eggs, and they all hatched, fewer than seven chicks will make it past their fourteenth-day birthday. Predators are a big problem, but weather is also a major issue. Cold, wet springs can take a toll on young turkeys. The good news is that if a chick does make it past those first few critical weeks, it has decent chance of living for several years, unless of course some bonehead shoots it or it is hit by a Subaru while walking along Station Ave. The oldest known Wild Turkey was a Massachusetts bird that lived to the ripe old age of fifteen. That’s pretty darn old for any bird, especially one whose name appears in so many cookbooks.

If only thirty-eight percent of the nestlings make it past their first two weeks, how were you able to see a family of eighteen (that you counted “three times”)? Well, either the female laid a massive clutch of about fifty eggs (good luck to her) or the flock you saw contained more than one family. I’m guessing it’s the latter. In the fall family units often join each other. The birds you saw were most likely several families combined. The flock probably contained two or three adult females, plus many young females and perhaps a few young male birds as well. Why did they all look the same? By mid-winter it can be tricky to tell the adult females from the young birds. The fat, more distinct adult males typically stay clear of these family flocks. They’re too busy at gobble camp to hang with the fam.

As for that “runt” you inquired about, Peggy, turkeys really don’t have runts. You are thinking of dogs or pigs. Large litters of mammals produce runts when smaller siblings can’t fight their way past their litter-mates to feed from their mother’s…umm, you know, milk faucets. It doesn’t work that way with turkeys. A few days after hatching young turkeys are quite capable of getting their own seeds and insects and don’t have to fight for a position at the milk faucets, which is a good thing for the mother. I’ve heard beaks can be painful.