Dear Bird Folks:

I’m still getting juncos coming to the feeders in my yard. Isn’t the end of April a bit late for juncos to still be around here? Is it the long winter that is keeping them here? Also, when they finally leave here where do they go?

-Gramma Jane, Shrewsbury, MA

Hey Gramma Jane, Cool name.

Are you the kind of gramma who bakes pies or are you an english teacher? No wait, I think that would be Grammar Jane. Forget I asked that question. You know this makes three questions in a row that I’ve gotten from central Massachusetts. You people sure are needy. Did Holy Cross close or something?

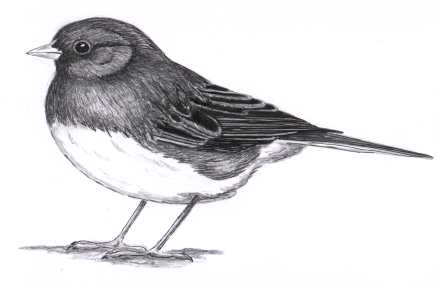

Juncos are one of the most abundant birds at feeders throughout the country, yet this common bird has caused a fair amount of confusion in the birding world. The U.S. has at least six different kinds of juncos, each outwardly so unique that they clearly seem to be different birds. Yet, where their ranges overlap the birds readily interbreed, forcing scientists to consider them one species. They have grouped all of our juncos into one major species called “Dark-eyed Junco,” which includes six distinct races. The familiar gray and white bird that we see here in the east is called “Slate-colored Junco.” If you are confused by all of this, you are not alone. Juncos have been confusing birders for years, even the ones from Holy Cross.

The Slate-colored Juncos can be found in every single U.S. state that doesn’t grow pineapples. Most juncos breed way up north in Canada and only visit the U.S. when the weather turns nasty. They form winter flocks that often remain together throughout the season. The flocks appear to have their favorite wintering grounds and will return to the same location year after year, providing a Walmart hasn’t completely black topped the area during the summer. People who are lucky enough to have a winter flock of juncos sometimes refer to them by the folksy name of “snow birds”, meaning birds that arrive with the snowy weather. But we should not confuse juncos with the other snow birds who travel south in Winnebagos.

Even though juncos spend their winters together in flocks, they are not always at peace with each other. They are constantly fighting for dominance while feeding. The more dominant birds are able to eat first. To avoid major conflicts juncos have developed three distinct wintering levels. Many of the young males winter in the north, where they are able to avoid the more dominant older males. Staying north can make for a long, tough, risky winter, but if they survive, it will allow them to be the first birds to return to the breeding grounds in the spring. The older males winter further south, avoiding some of the coldest weather, but still close enough to the breeding grounds so are they are able arrive in time to stake out a territory. The females, being the smart ones, spend their winters well south, thus avoiding the cold weather and the food competition from the aggressive males.

The juncos that you are seeing in late April or early May are most likely females. They know what is waiting for them up north and are in no hurry to start breeding and dealing with screaming kids.

Even though the majority of juncos breed in Canada, a few states, including Massachusetts, have a summer nesting population. Your juncos will be gone soon, but they will only be a few towns away. Berkshire County has plenty of them, with a few nesting in some of the higher elevations of Worcester County. If you need to see Juncos in July Gramma Jane, take a short trip to Western Mass. But be sure to bring them a pie when you go. Or better yet, send me the pie and I’ll make sure they get it.