Dear Bird Folks,

Every spring a pair of Mallards arrive on a tiny pond near my house. They are there for a few weeks and then they disappear. Do you think they are nesting nearby? Also, do you think they are the same birds I see year after year?

– Tobin, Orleans, MA

Thanks, Tobin,

I totally appreciate that you asked a question about Mallards. It’s not that I have a particular affection for these birds, but I love that they have a short name. A few weeks ago I had to write about Black-billed Magpies; the week before it was Common-ground Doves. Those names are just too darn long to type over and over. Writing about the Mallard, a bird with a simple name, is a piece of cake. It will only take me two minutes to write this column, instead of the usual three minutes. I know it sounds trivial but long names take their toll. That’s why we see more magazine stories about Madonna than we see about, say, Jo-Jo the Dog Faced Boy. Jo-Jo is clearly a far more interesting person but Madonna gets all the press because of her short name. It’s not fair, but it’s true. The other reason I like Mallards is that it’s nice to write about a bird that everyone knows. Next to the Aflac Duck and Duck à l’Orange, Mallards are the most recognized and abundant wild ducks in the world.

The reason these ducks are so widespread is because they aren’t fussy about where they live. Their nesting habitats range from swampy wetlands, to tiny vernal pools, to man-made inner city ponds. They also aren’t fussy eaters. Vegetation, bugs, chips or whatever is on the local menu suits them just fine. They aren’t fussy breeders, either. Mallards don’t need candles and soft music to get themselves in the mood. Heck, sometimes they don’t even need each other. Mallards are notorious for interbreeding with other duck species. In fact, the movie Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner was originally about a Mallard and a Wood Duck couple before Hollywood tweaked it a little.

Unlike some waterfowl, like Mute Swans, which stay together year in and year out, Mallards only hook up for a single season. For them it’s one and done. Each fall Mallards get together in large flocks and begin the process of selecting a new mate for the following spring. They perform an assortment of wild courtship displays until pairs are formed. Once paired off the new couple has their own mating rituals, and one of these is called the “inciting” display. Here the female follows the male around, no matter where he goes. It sometimes looks as if he’s trying to get away from her and I understand why because she is yapping in his ear the entire time. This is unique because most other females save their nagging until after the wedding. And no bird can nag better than Mrs. Mallard. Her voice is the quintessential duck call. Any TV show, kid’s toy or cartoon that needs a duck call uses the voice of a female Mallard. The classic, loud “quack, quack, quack” is exclusively hers. The male’s voice, conversely, is softer and less harsh. His quiet quack has an up-note at the end, almost like he’s asking a question (probably, “Is she ever going to shut up?”).

When spring arrives it’s the female’s job to look for a place to build a nest, and now it becomes the male’s turn to follow her around. Like most ducks, Mallards need to be close to water, but not all couples can afford waterfront property. So the female will pick a spot as close as she can get, which may be in a brushy or wooded area a few hundred yards away from water. Here’s where things get interesting. After being together for most of the winter, the Mallard couple separates. While she alone builds the nest and lays the eggs, the old man stakes out a territory in a nearby pond or woodland pool. His job is to defend this feeding area so the female will have a place to rest and eat in between her nesting chores. When she needs a break from her motherly duties, she’ll fly to his territory and the two will have lunch together, much like any married couple. However, all this marital bliss ends the moment all her eggs are laid. Now she has no time for the male and will drive him away from the very pond he has been protecting for her. After fighting with her for a bit the male decides he doesn’t need the hassle and moves on. Where does he go? He usually spends the rest of the season at the local pub trying to figure out what went wrong.

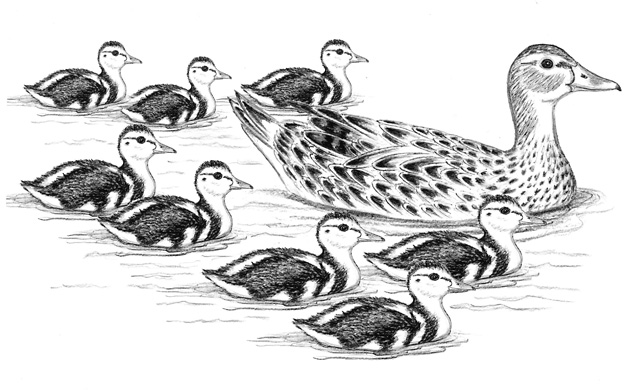

Following three weeks of incubation the eggs hatch and the excitement begins. It only takes a few hours for the ducklings to get their bearings, learn their names and imprint on their mother. At this point the hen will lead her very young family to the nearest water. Her path can be through the woods, or a backyard or across a city street, creating cute photo opps and great material for a children’s book.

Yes, Tobin, I do think there is nest somewhere around that tiny pond near your house, but good luck trying to find it. The hen is very good at camouflage. While I doubt you are seeing the same Mallard couple from last year, there is a good chance it’s the same female. Hens often return to the same nesting location if they were successful the year before. However, they typically don’t return with the same male. Last year’s male is likely busy trying to pay off the bar tab he ran-up at the local pub.