Dear Bird Folks,

I read in one of your past columns that hawks are sometimes a problem at bird feeders. I also read that several falcons, called “Merlins,” have been spotted in my area. Could these Merlins be a threat to my backyard birds?

– Jackson, Westbrook, CT

Wow, Jackson,

You sure read a lot. But I’m glad you do because this gives me an opportunity to go into my annual “don’t blame the birdseed” tirade. Yes, hawks are a problem at bird feeders. An attack from a hawk, usually a Sharp-shinned or a Cooper’s Hawk (we’ll get to Merlins in a bit), will cause feeder birds to abandon an area. This can be a problem anytime of year, but for some reason it seems to be worse in December. Last month my feeders were packed with birds. Then a Sharp-shinned Hawk started hanging out and now the birds in my yard are as rare as a package of Twinkies at the grocery store. And this problem isn’t unique to me. It can happen to anybody, even to people who insist, “It’s never happened before.” Well, guess what. I’ve never had gray hair before either. Stuff changes. What can we do when hawks invade our yards? Not too much. Eventually, the hawk will move on and the birds will return. In the meantime, keep the food in your feeders fresh and don’t blame the birdseed. I repeat, don’t blame the birdseed. The problem is never the birdseed. (Unless, of course, you use one of those crappy mixtures. Then you get what you deserve.) There, I’ve stated my case for yet another year. Now on to Merlins.

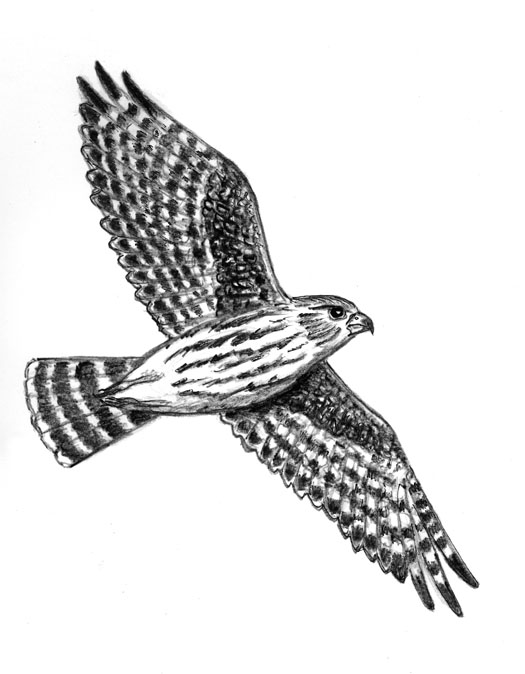

Merlins are small falcons, but don’t let their size fool you. These little birds are tough. Weighing only about six ounces, Merlins are like a cross between Jimmy Cagney and a honey badger. During the nesting season they are even more aggressive and seem to look for trouble. I think of them as the neighborhood punks. (Some naturalists refer to them as “cantankerous,” but I don’t know how to spell that so I go with punk.) They are so dominating that some larger birds, like the harrier (aka, Marsh Hawk) for instance, will build a nest near nesting Merlins. The mother harrier doesn’t need to worry about ravens and other predators stealing her eggs with a flying Jimmy Cagney patrolling the ‘hood.

Merlins also have one of the coolest names in the avian phonebook. The name “Merlin” conjures up a sense of mystery, power and magic. And while this bird has nothing to do with King Arthur’s wizard, it does possess a bit of mystery and an awful lot of power. (They perform no real magic, though, except at the occasional party.) The name Merlin is actually derived from the old French word “esmerillon,” which I’m sure translates into something interesting, but don’t ask me what. I’m only fluent in new French. When I first started birding Merlins were called “pigeon hawks.” I thought for sure it was because they preyed upon pigeons. It made perfect sense to me. But the fact is Merlins rarely eat pigeons, mostly because pigeons are bigger than they are. (Plus, they’re pigeons. Would you want to eat something that lives under a bridge?) Merlins are called pigeon hawks because they are robust and stocky, and look very much like pigeons when they fly. I know that’s not the most exciting bit of trivia you’ve ever read, but come on, not everything can be as thrilling as learning that “esmerillon” is an old French word.

Like most falcons, the Merlins’ food of choice is birds, usually small songbirds or shorebirds. However, they have a different hunting style than that of their larger cousins, Peregrine Falcons. We’ve all seen video clips of a peregrine’s supersonic dive onto unsuspecting prey. Merlins aren’t as dramatic. They typically sit on a perch, wait for a bird to fly by and then go tearing off after it. In many locations Merlins have learned to let other hawks do some of the work for them. The observant falcon waits for a slower hawk to startle a small bird from its hiding spot. The speedy Merlin then says, “I’ll take it from here,” turns on the jets and the chase is on. Hunters have long used birds of prey for the rather traitor-ish activity of falconry. (I’m sure there’s a special place in bird hell for any bird that captures one of its fellow birds for the entertainment of humans.) But Merlins are rarely used for this so-called sport. Their smaller size means that they can only catch small prey, like songbirds, and hunting songbirds isn’t very macho, even for a falconer.

In the Northern Plain states Merlins have moved into suburban settings, where they find the ubiquitous House Sparrows to be a reliable food source. But it doesn’t appear the same thing has happened in the East. Here Merlins tend to hunt along coastal dunes or in open areas away from people. Because of this habitat preference, Jackson, I wouldn’t worry too much about Merlins being a threat to your backyard birds. As I said earlier, you are far likelier to have Cooper’s Hawks or the similar Sharp-shinned Hawk bothering your feeder birds. Five minutes after I started writing this column a Sharp-shinned Hawk blasted through my yard and I haven’t seen a feeder bird since. But I’m not worried. I know they’ll return. The birds always return. It’s too bad I can’t say the same thing about Twinkies…sigh!