Dear Bird Folks,

What is a “moonbird”? I’ve heard this name mentioned and assume it is some kind of owl, but which one?

– Ted, Wareham, MA

Spock would be proud, Ted,

Your thought about a moonbird being a species of owl is “logical.” After all, owls come out after dark and hunt by moonlight. But in this case a moonbird isn’t an owl or a bird that hunts at night; it’s a bird that actually has flown to the moon. Seems impossible, right? But it’s true…well, sort of. I’ll explain.

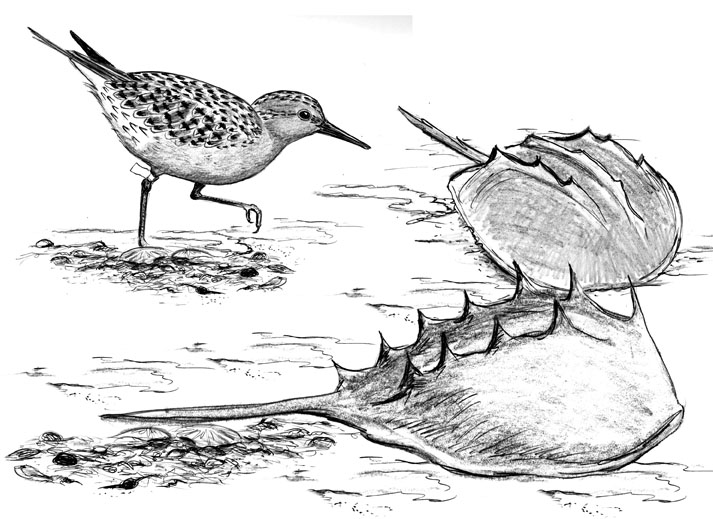

As you know, many birds have a spring and a fall migration. Some birds fly hundreds, thousands and even tens of thousands of miles as they travel from their wintering grounds to their breeding grounds and back. Some of these super-migrants may, if they live long enough, eventually fly the equivalent of a trip to the moon; hence, the name, “moonbird.” One of these over-achieving birds is the Red Knot. Knots are medium-sized sandpipers that spend their winters on the southern tip of South America and their summers in the high Arctic, a round-trip of nearly 20,000 miles. Occasionally, a knot will survive enough of these epic journeys, and accumulate enough air miles to obtain moonbird status. Then there is “B95,” a knot that has defied all odds and has accrued nearly enough miles to fly to the moon and back, a distance in excess of 400,000 miles. The fact that this five-ounce sandpiper has been able to fly that many miles in its lifetime is amazing in itself. But add in the fact that this bird is a member of an endangered species and that most of its fellow knots have vanished from the planet, and the whole thing is kind of mind boggling.

In the spring this subspecies of knots leave their wintering grounds in Tierra del Fuego and head north. After a few short stops to eat and rest, they depart and attempt to make a 5,000-mile trip to Delaware Bay, right here in the U.S. of A. To make this trip the birds travel nonstop for four straight days and nights, without sleeping, eating or drinking. It’s like a flight on United Airlines, only the birds are usually on time. And being on time is the reason why the birds fly so far and so fast.

It’s critical for the knots to time their arrival on Delaware Bay with the breeding cycle of horseshoe crabs. Yes, horseshoe crabs, those weird things that look like old army helmets with tails are extremely important to Red Knots. Each spring the world’s highest concentration of Atlantic horseshoe crabs lay their eggs on the beaches along Delaware Bay. It is these eggs the knots are seeking. The protein-packed eggs give the birds the energy they need to continue on for the last 2,000-mile leg of their journey to the Arctic. For centuries this crab/knot thing has worked perfectly, then some creature screwed things up. Wanna guess what the creature was? Yup, it was humans. Surprise!

In Allison Argo’s eye-opening documentary, Crash: A Tale of Two Species, she tells how the crabs and the birds were both doing fine until the 1990s, when the local fishermen started “harvesting” the crabs…not for food, but for bait. Millions of horseshoe crabs were pulled out of Delaware Bay and chopped in half before they had a chance to lay their eggs. As a result, the horseshoe crabs went into decline, and when the knots arrived there was nothing for them to eat. After a 5,000-mile nonstop journey the famished birds found that their version of Stuckey’s was closed and there were no alternatives. Without the crab eggs to feast on, the knots weren’t strong enough to continue on to their breeding grounds, and their population plummeted. Not good.

As the knots steadily disappeared from the Delaware Bay beaches, one stubborn bird continued to return year after year. It was our pal from five paragraphs ago, good old B95. Hatched in 1993, B95 was first captured in 1995 and given its namesake leg band. Over the coming decades this one Red Knot was recaptured and/or spotted many times as it continued to make its annual trek from Argentina to northern Canada. It eventually became the subject of a book by Phillip Hoose, appropriately titled, Moonbird. The book tells us how this lone amazing bird continues to hold on while, sadly, most other Red Knots have vanished. But, there is a bit of good news.

As a result of Hoose’s book and the work of Manomet’s Brian Harrington, plus Allison Argo’s documentary and help from many others, the horseshoe crab harvesting has been regulated and now some of the crabs are breeding once again. Also, in November 2014, the Red Knot finally received federal protection under the Endangered Species Act. So, are things getting better? Funny you should ask. This past Monday, a woman who just happens to be married to the above-mentioned Brian Harrington, came into our shop (we get all the big shots). She indicated that perhaps the efforts are paying off, as more migrating knots are being seen. Yay!

It makes sense that owls should be called moonbirds, Ted, but in this case the title has been reserved for long-lived, long distance migrants; in particular, one amazing Red Knot. And as far as we know, B95 is still making his nearly impossible annual journey. Hopefully, next spring he will once again arrive on Delaware Bay and with any luck he’ll be on time. But that will only happen if he can avoid storms, predators and flying United Airlines.