Dear Bird Folks,

Do oystercatchers ever journey inland? I live in an area that attracts lots of migrating shorebirds, but not once have I seen an oystercatcher. Do you know if oystercatchers use any of the Great Lakes on their migration, so I might get to see one, or should I forget about it?

– Vinny, Rochester, NY

Yo, Vin,

Oystercatchers in Rochester? Fuggedabouit. It ain’t happenin’. Capice? No, wait. People from Rochester don’t talk like that. I’m thinking of a different part of New York. Let’s start over. Hi Vin, thanks for writing. I don’t blame you for wanting to see oystercatchers. They are impressive looking birds. But with the exception of Wegmans Food Markets, there aren’t a lot of oysters living in Upstate New York, and that’s a problem for birds that like to catch them.

For those of you who don’t know, the American Oystercatcher is a shorebird. It is a shorebird in every sense of the word. It eats, sleeps, and breeds along the shore and is rarely found away from it. And the shore I’m talking about is the real shore, not the lake shore, or river shore or Dinah Shore, or Pauly Shore. Definitely not Pauly Shore. An oystercatcher may live its entire life within sight of the ocean. They spend each day hanging out at the beach eating shellfish. I’d bet there are lots of people who wouldn’t mind coming back as an oystercatcher. That wouldn’t be a bad option. It’s certainly better than coming back as a shellfish, or Pauly Shore.

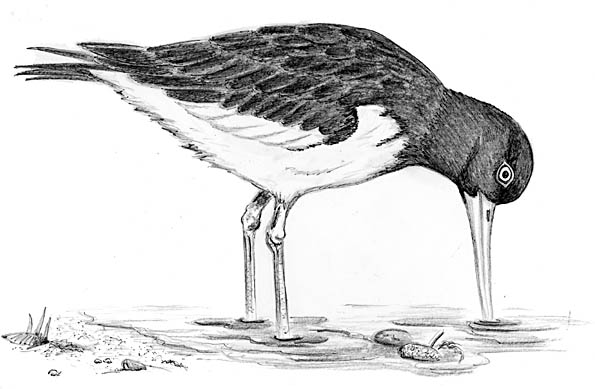

For bird watchers oystercatchers are a dream bird. Not only do they have an envious life-style, but they are extremely identifiable. Many shorebirds can be maddening to figure out. Take a look in any field guide and you’ll see what I mean. Every shorebird on the page looks the same, at least they do to me. This is not the case with the oystercatcher. It is a tall bird, with a chunky body, a pure-white belly, solid brown back and a jet black head. The bird also has a crazy bright-yellow eye that makes it look like a character that has escaped from a Stephen King novel. But the most impressive feature is the bird’s beak. It is quite long, stocky, and brilliant orange, making the oystercatcher appear as if it is eating some kind of giant carrot. Now that I think of it, this carrot-beak could explain why the bird is not found inland. It may have a fear of rabbits. I can see that.

It is with this gaudy beak that the oystercatcher is able to earn its living. They spend much of their day probing coastal salt marshes and mudflats looking for clams, mussels and yes, oysters. I don’t know if you have ever tried to bust into an oyster before, Vinny, but it’s not easy, even if you have the right tools, and nearly impossible if you don’t. Yet, this little one-pound bird, without the use of tools or hands, can open the toughest oyster in matter of seconds. If the oystercatcher spots an oyster that isn’t completely shut, the bird instantly jams its bill into the opening before the oyster can clam-up. The bill then snips the bivalve’s powerful adductor muscle, which holds the two shell halves together. Without the adductor muscle the oyster has major problems. If an oystercatcher finds an oyster that is already closed, that doesn’t stop it. With a few sharp blows from that crazy orange bill, the bird pokes a hole in the shell, again snips the adductor muscle, adds some cocktail sauce and lunch is served.

American Oystercatchers typically build their nests on sandy beaches or in nearby dunes. Even though the birds themselves are fairly conspicuous, when it comes to building a nest they are strict minimalists. Their nests are nothing more than scrapes in the sand with occasional bits of broken shells added in a feeble attempt at interior decorating. Oystercatchers might not be very hip homebuilders, but their social life is extremely broad-minded. If the local number of breeding adults is high, oystercatchers will sometimes form a threesome, in which one male breeds with two females. The two females and the one male all share the same nest. That may sound kind of kinky to us, but what else would you expect from a bird that spends its entire life eating oysters?

When it comes to migration oystercatchers are once again minimalists. Throughout much of their range they don’t migrate at all. Only birds spend their summers north of Virginia move south when winter comes. Because of their short migration tendencies and love of the coastline, the odds of seeing an oystercatcher around Rochester aren’t great. A better way to see them, Vin, is to plan a trip to Cape Cod. We have lots of oystercatchers during the warmer months. I think parts of Long Island also have oystercatchers. As it turns out, oystercatchers are well-liked birds throughout New York and I can see why. Their broad-minded mating habits make the oystercatcher a natural candidate for governor.