Way back last week…

A lady named Pam, from Norwalk, CT, wrote in asking about Passenger Pigeons, a bird that has been extinct for exactly ninety-three years and sixty-nine days. In light of the possible existence of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, she was wondering if there could be a population of Passenger Pigeons living undetected somewhere in the world…to which I blurted out: “Nope. There is no chance of a single Passenger Pigeon living anywhere in the world.” Obviously, I was in an abrupt mood last week. There’s something about forced extinction that taints my normally sweet disposition.

Just in case anyone out there misplaced their eyeglasses and couldn’t read last week’s column, let me do a quick review. When the European settlers first arrived, the Passenger Pigeon, a bird that looked much like a Mourning Dove, was by far the most common bird on the continent, and perhaps the entire world. Their numbers were in the countless billions and most of this massive population was confined to the eastern half of North America. Then, in a very short period, the Passenger Pigeon population went from billions to zero. How is that possible, you ask? Oh, the answer to that is easy. We killed them all. We might not be able to make Christmas tree lights that work for more than one season, but we sure know how to kill stuff.

Back before there were Super Stop & Shops and 7-Elevens, early Americans had to find and gather their own food. Whatever they could catch ended up in the frying pan and the frying pans were extra busy whenever a flock of Passenger Pigeons came by. The sheer numbers of passing birds made for easy hunting. Fortunately for the birds, the size of their flocks was so massive that hunting for the dinner table had little effect on their overall population. Then one day someone figured out that if they killed a few extra birds, they could eat some and sell the rest to the rich city folks. (Those darn city folks!) The minute commercial hunting took hold the Passenger Pigeon was in big trouble.

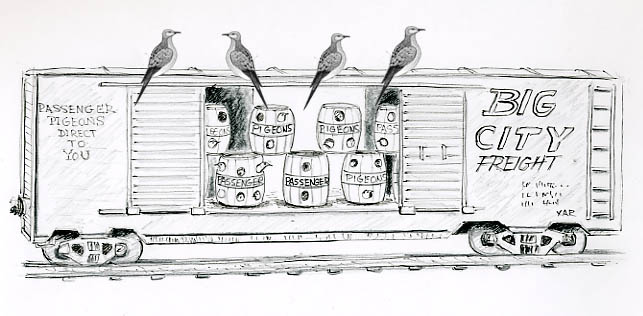

Encouraged by the handsome price of two cents per bird, many people quit their jobs as wig makers, or whatever people used to do back then, and headed out after the birds. They used guns, clubs, nets, smoke and fire to scoop up as many birds as they could to sell to those darn city folks for two cents a piece. At first, market hunting had little effect on the birds, but that all changed with the introduction of the railroads and the telegraph. Now hunters had a way of getting the freshly killed birds to market, which they shipped by the freight carload. And no matter where the birds went, a few dots and dashes over the telegraph wire quickly alerted gunners to their location.

Eventually, there were fewer and fewer places where the great flocks of Passenger Pigeons could rest and feed without being blasted. More importantly, there was no place where the birds could breed in peace. Passenger Pigeons nested in immense colonies, which often covered several hundred acres. But before the birds could build a nest and raise their chicks, swarming market hunters forced them to abandon the colony.

In addition to market hunting, the birds had other problems to deal with. Deforestation for farms, pastures and lumber took away much of the their food supply and nest sites. The birds’ gregarious lifestyle may have been another factor in their demise. Passenger Pigeons did everything in massive flocks. As their population was reduced, the smaller flocks just weren’t as successful at locating feeding and nesting areas.

Why wasn’t something done to save the birds? Even if people wanted to protect the birds, which they really didn’t, it was simply too difficult. They couldn’t just close the beach for a few weeks, like at least some people want to do to save plovers. Passenger Pigeons were extremely nomadic. It was impossible to protect their ever-changing locations. And let’s not forget about greed. Much like today, nobody wanted to do with less for the sake of future generations. As recently as 1878, a single hunter shipped three million Passenger Pigeons to market. Twenty-two years later there were none.

In 1900 the American Ornithological Union offered a reward to anyone who could find a nesting colony of Passenger Pigeons. The reward was never collected. The only Passenger Pigeons that remained were in zoos. But without the stimulus of the flock the captive birds wouldn’t breed. The zoo birds slowly grew old and died. The last living Passenger Pigeon, “Martha,” slipped into history at 1:00 PM, on September 1, 1914, in an aviary at the Cincinnati Zoo. This marks the only time we knew the exact moment a species became extinct.

The reason I feel certain there are no more Passenger Pigeons, Pam, is because the birds simply couldn’t exist in a small hidden flock. They were nomadic birds that needed to wander in large numbers in order to be successful. Two of each may have worked for Noah; but unfortunately, it just didn’t do it for these birds.