Dear Bird Folks,

I recently watched a documentary titled The War of the Birds, about the carrier pigeons the British used in WW II. I really enjoyed it and learned quite a bit about pigeons at the same time. If you haven’t seen this movie you might want to track it down.

– Claire, Plymouth, MA

I hadn’t, Claire,

I had never even heard of The War of the Birds and I thought I knew all the movies about birds. Based on your suggestion, I quickly found the movie online and watched it from beginning to end. If there is anything I like nearly as much as watching birds, it is sitting and watching movies…about birds. Bird movies are way better than watching prime time television. This documentary about awful WW II was still less violent than those nasty crime shows the networks keep cranking out. I’m not sure what a discussion about bad TV has to do with pigeons, but I just felt like saying it.

This first thing that caught my attention in the movie is that during the war the British raised over 250,000 pigeons. Pigeons? That’s right, stinky old pigeons. Aren’t pigeons the bird most people want to get rid of? Well, as it turns out, the British not only wanted pigeons, but several thousand servicemen owe their lives to these stinky birds. How is that possible, you ask? World War II was the first war to feature widespread use of wireless communication. But this new method of communicating wasn’t perfect, so there needed to be a plan B. Plan B was using carrier pigeons. RAF bombers, for example, carried two pigeons on every bombing run just in case they needed backup. On one particular bombing run backup was indeed needed, as a pigeon named “Winkie” saved an entire flight crew. This one bird not only saved the crew, but Winkie had the best name of any wartime hero, ever.

On a late night run, the ill-fated bomber crashed somewhere in the North Sea. The crew survived the crash, but had no way to radio for help. They just helplessly bobbed around in the icy water. British rescue teams searched, but came up empty and eventually gave up looking. Then good old Winkie arrived at headquarters and the search was back on. Somehow, the crew was able to release their backup communication device, which incredibly flew 120 miles, over the open ocean, in pitch black, while covered in seawater and oil. By factoring in wind speed, ocean currents and the time it took Winkie to fly the 120 miles, officials were able to narrow down where the plane crushed and the entire crew was eventually saved. After they recovered from their injuries, the thankful crew held a special dinner, with Winkie as their guest of honor. Winkie was served a meal of cracked corn and he was thrilled. (I just hope, on this one particular night, the chef had the good sense not to serve the other dinner guests barbecued wings.)

In another instance, the British Army had captured a German-held town in Italy. Unfortunately, the U.S. Air Force didn’t know about the Brit’s success and was getting ready to bomb the town…in twenty minutes! Upon learning of the bombing the British tried desperately to contact the Americans on the wireless, but to no avail. (Their provider must have been AT&T.) So, the Brits released a carrier pigeon, by the name of “G.I. Joe.” (G.I. Joe is a good name, but it’s no Winkie.) The bird had only twenty minutes to fly to the Air Force Base, which was twenty miles away. This meant Joe couldn’t get lost, veer of course or stop for snacks at any Italian birdfeeders. When the bird arrived – in twenty minutes – the bombers were taxiing down the runway. The Americans read the message and quickly aborted the mission, and over a thousand British soldiers were saved. Nice job, G.I. Joe.

At the beginning of the war nearly ninety-eight percent of the carrier pigeons were able to deliver their messages. Then the Germans enlisted the help of the pigeons’ worst enemy, Peregrine Falcons. The falcons had a big impact on the pigeons, but they didn’t stop them. Many of the Brit’s birds could out-fly and out-maneuver the German falcons. (When it came to pigeon breeding, it was the British who produced the master race.) One pigeon, by the name of “Mary of Exeter” (they must have run out of normal names), was struck by a falcon, but managed to escape and completed her mission. Mary’s injuries were so severe that it took twenty-two stitches to close her wounds. At this point, you would think Mary’s fly days would be over, but this was wartime and she was British. As soon as Mary’s wounds had healed, she was sent back out. For the balance of the war she continued to fly for the cause and continued to dodge the falcons. Mary of Exeter survived the war and lived until 1950, when she peacefully died of old age. How about that?

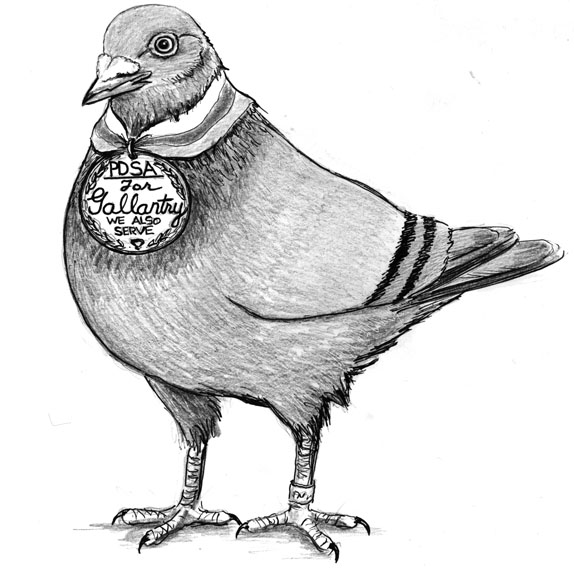

Thanks for suggesting The War of the Birds, Claire. It was interesting to learn that from D-Day to the Battle of the Bulge, pigeons provided critical information that undoubtedly saved thousands of lives. In fact, the British award medals for wartime gallantry and one medal is specifically given to animals. Yes, animals. It’s called the “Dickin Medal,” named after Maria Dickin, who worked tirelessly for animal welfare. Wanna guess which animals won the most medals? By the end of 1947, thirty-two medals were awarded to pigeons, followed by eighteen to dogs, three to horses and at the very end of the list, winning one lousy medal, a cat. Can you imagine honoring a cat? I know it’s only one medal, but if you ask me, it’s one too many.