Dear Bird Folks,

There is a bird singing in my yard that I can’t identify. I have not been able to see the bird, but I hear it every day. The song is a rapid “dee, dee, dee, dee, dee,” which quickly rises up the scale. It reminds me of a singer warming up before taking the stage. Any help would be appreciated.

– Adele, Truro, MA

I don’t know, Adele,

Oh, I know what bird you are hearing, but I don’t know if I can write about it. It’s too depressing. Let me explain. Your mystery bird is a Prairie Warbler. For years Prairie Warblers have nested in the yard next to mine. On any given summer morning I could lie in bed and hear the male’s delicate song. Then one summer the singing stopped and I heard no warblers from bed. Even when I got out of bed, at the crack of 10:30 AM (I like to get up early in the summer), I still didn’t hear them. The birds had simply not returned. A few days later I drove to the Lower Cape’s hotbed of Prairie Warbler activity, the National Seashore’s Marconi site. But no warblers were singing there either. What the heck? Something really bad must have happened to them. That’s when I discovered the sad truth, and it had nothing to do with the birds.

As I walked around the Marconi site, I noticed a bird sitting on the top of a nearby pitch pine. I could easily see it was a Prairie Warbler. Yea! That’s the good news. The bird appeared to be singing, but as it opened its mouth, no sound came out. What was wrong? Had the warbler lost its ability to sing? Was it doing an impression of Marcel Marceau or Harpo Marx? No, the bird and its voice were fine. The problem was my ears. They had lost the ability hear the warbler’s high notes. The bird was singing its heart out but the only sound I could hear was the wind coming off the ocean, and some guy’s beagle barking at a pinecone. The only thing sadder than a birder with bad ears is a beagle needing glasses. (Hey, I wonder if a vision-challenged beagle can get a seeing-eye dog. That’s worth looking into.)

Prairie Warblers are regular summer visitors to Cape Cod, the key word being “summer.” They typically don’t arrive until late May and are mostly gone by the end of September. But don’t let the bird’s name fool you; Prairie Warblers hate prairies. Prairies are hot, dry and reek of buffaloes and the birds want nothing to do with them. They are most often found breeding in overgrown fields and in the slow growing vegetation of coastal dunes. When the settlers first arrived in eastern North America, they found big trees and very few Prairie Warblers. But that eventually changed after the settlers did what they do best; clear-cut the forests. Go to any local bookstore and you’ll find books filled with turn-of-the-century photos of Cape Cod. Back then this wasn’t a very appealing place for either people or birds. With the forests stripped away, ol’ Cape Cod looked like a bad golf course. As bushes and small trees grew back, the Cape became ideal nesting habitat for Prairie Warblers. By 1960 they could be heard singing – even by me – from just about any location on the Cape.

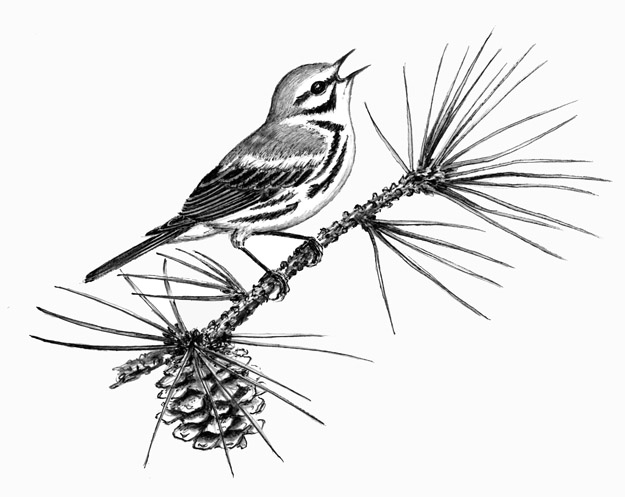

Prairie Warblers are attractive birds, but not striking. The males are mostly yellow, with a few black lines along their sides. They also have a black semi-circle under each eye. It resembles the black stuff athletes put under their eyes to help stop sun reflection, and to look cool. A good way to identify Prairie Warblers is to look at the tail. They have the habit of constantly wagging their tail up and down. However, the best way to find them is to listen (sigh) for their song. As you have described, the male warblers have a thin, high-pitched song that sounds like “zee, zee, zee, zeeeee” (or “dee, dee, dee, dee”), which rises up the scale faster and faster until it disappears altogether.

Male Prairie Warblers typically return to the same nesting site each spring, but this is not always true for the females. Some lady warblers pick a new location and a new male each year and that’s fine with the boys. They are more than happy to mate with a brand new female each spring. Perhaps that explains why their tails are always wagging. Over the past fifty years the population of Prairie Warblers has been dropping. One of the reasons for their decline could be that overgrown fields have turned into mature forests. Our local Prairie Warbler population is also in decline, but recently the Park Service has been doing some selective cutting in an effort to keep large trees from totally taking over. Hopefully, this will keep these birds coming back to the Outer Cape.

Unfortunately, the same can’t be said for my hearing. It’s not coming back. High-pitched sounds are no longer within my range. The books say hearing loss has to do with aging and exposure to loud sounds. Aging can’t be the problem, since I’m not getting any older. Loud sounds are probably the culprit. Although my parents claim that I listened to too much rock and roll as a teenager, I think my hearing problem has to do with squirrels. All the years I’ve spent listening to customers scream at me about squirrels has been enough to make anyone’s ears shutdown.