Dear Bird Folks,

I’ve recently moved to Cape Cod and have decided to get into birding. In particular, I want to learn to recognize sandpipers. Which sandpiper would be the easiest for me to identify first?

– Kyle, Dennis, MA

You are brave, Kyle,

You aren’t brave to move to Cape Cod; that’s a good thing to do. I think you’ll really like it here (besides I can use a few new customers). You are brave to jump right into studying sandpipers. I’ve been here for over forty years and I still can’t figure all of them out, as many of the Cape’s thirty-five or so sandpipers and plovers are quite similar looking. For example, there is one sandpiper that goes by the name of “Greater Yellowlegs.” That bird is fairly easy to identify until you try to distinguish it from its nearly identical cousin, the Lesser Yellowlegs. Or how about Long-billed Dowitcher versus Short-billed Dowitcher? Good luck with those two clones. Then there are the tiny sandpipers. These sparrow-sized birds look so similar that many bird watchers simply call them “peeps” and let it go at that. But I’m going to start you off with an easy one, the Ruddy Turnstone. This sandpiper has field marks that are so obvious that even I can identify it…most of the time.

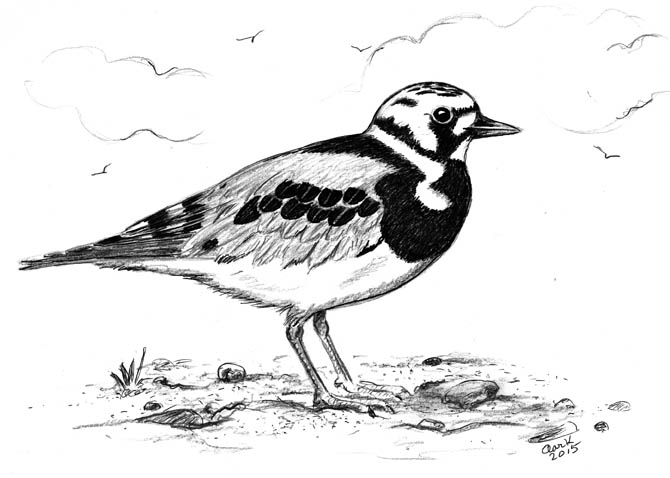

The Ruddy Turnstone has two things going for it: its striking plumage and its real cool name. The name Ruddy Turnstone sounds like a security guard for the Royal Family: “Before you see the Queen, you first have to pass by the Ruddy Turnstone.” (But that could be just me.) In breeding plumage this bird is unmistakable. It has bright orange legs, a white belly, a black bib, a chestnut back, and a black and white head that looks like a cross between a clown and Skeletor. The body shape is elongated, like a sweet potato with a beak. Speaking of beaks, most sandpipers have long beaks that they use for probing deep into the sand. But the turnstone has a short, sturdy beak, which it uses to…you guessed it…turn over stones. When searching for food turnstones are often seen energetically flipping over stones, shells and seaweed, looking like me trying to find the car keys on my messy desk.

Turnstones are found on Cape Cod anytime of year, but they are most frequently seen here in the summer. Yet, the birds we see in the summer are either migrants or non-breeders, because the breeding birds are way up in the high Arctic busily building their nests. A nest can be a complicated process for many birds, but the turnstone’s nest is merely a scrape in the ground; the scraping itself, however, is actually part of their courtship ritual. To impress his mate, the male will make several scrapes for the female to inspect. But even if he makes a hundred scrapes, she’s never going to be interested in any of them (some ladies are never satisfied). The stubborn female would rather do her own nest scraping, which she eventually does right before she lays her eggs. Poor scraping skills aside, the male is actually a significant partner in the breeding process. He even forms a brood patch so he can do his fair share of incubating. (FYI: A brood patch is a featherless area on the belly that helps transfer body heat to the eggs. It’s an important feature, but not very flattering.)

The dedicated male will continue to help keep his chicks warm even after they hatch. However, he doesn’t feed the baby birds, and neither does the mother. From day one the baby turnstones find their own food, while the adults provide protection from the Arctic weather and the numerous predators. After a week or so of providing childcare, the female gets tired of it all and leaves the breeding area. The dad must now do all the parenting by himself. As he watches his mate fly away, the dejected male is probably thinking, “If I could only make a decent scrape in the ground, I wouldn’t even need her.”

Eventually the male will also head south, and soon the chicks will follow. Turnstones spend their winter along the coast from Cape Cod to South America. Some hardy birds will actually make the 3,500 mile flight from the Arctic, across the Pacific Ocean so they can spend the winter in Hawaii, where they are know as “‘akekeke.” I have no reason to tell you that last bit of info, but how could I pass on a chance to write “‘akekeke”?

Where are the best places to see Ruddy Turnstones? A good place to start is any beach or mudflat that is not crowded with people (or their pets). You should begin to look for them soon, however. As the season wears on, the birds lose their handsome colors. A few evenings ago I was on one of Dave Bessom’s famous Nauset Marsh cruises and found a turnstone feeding with a flock of “peeps.” This bird was in full breeding plumage and was quite a looker. I was pretty excited that I had spotted such an attractive bird…until the next day when I read that someone else had seen twenty-two turnstones feeding along Cape Cod Bay. That will teach me to read.

Welcome to Cape Cod, Kyle, and good luck with your quest to learn about the Cape’s shorebirds. It won’t be easy, but if you work at it and focus on one bird at a time, you’ll eventually learn to identify all thirty-five of them. Just look at me. It may have taken me forty years of studying, but today I can easily identify all of our shorebirds…well, except for maybe thirty-three or thirty-four of them.