Dear Bird Folks,

I was reading some of your past columns online, when I noticed one from a few weeks ago that I believe had an error in it. The question was from Noah in NY. Noah asked if there are any birds that migrated up to North America after nesting in South America. You said a lot of things, as usual, but you basically said that no South American birds migrated to North America after nesting. Well, a few years ago, while on a whale watching trip, I remember the ship’s naturalist saying that some of the seabirds do leave the Southern Hemisphere after breeding, We were told that many of the birds we saw on the trip did a “reverse” migration. Care to comment?

-Doug, Hazleton, PA

Oh, come on, Doug,

Are you telling me that you are going to take the word of a part-time whale watching naturalist over your old pal, the Ask the Bird Folks guy? I’m shocked. Those whale people are so hopped up on Dramamine and sunscreen that I’m surprised they can even stand, let alone ID seabirds. And besides, when you work on a whaleboat, how much do you really have to know? There are only about four different whales to learn. There’s Humpback Whales, Finback Whales, Moby-Dick, Free Willy, and that’s it. A whale watch naturalist? Oh, please.

Of course. I’m kidding. Several of my best friends work on whaleboats. And though I hate to admit it, every one of them knows more about nature than I ever will. So yes, the whale person who told you that some southern seabirds migrate to the Northern Hemisphere after nesting was correct. However, in my defense, I was referring to land birds only, not seabirds. Take a look at the column if you don’t believe me. Just after word number 638 in my answer, you’ll notice I wrote “land birds.” Go ahead, check it out. There, that should keep the doubters busy for awhile.

When we think of seabirds we may think of powerful gannets, the aggressive skuas, or the graceful albatrosses which soar across the open seas on their huge wings. But the most common seabird in the world is the tiny Wilson’s Storm-Petrel. These little birds aren’t much bigger than a bluebird, but they are more than well equipped to handle a world of endless storms and ever-changing weather.

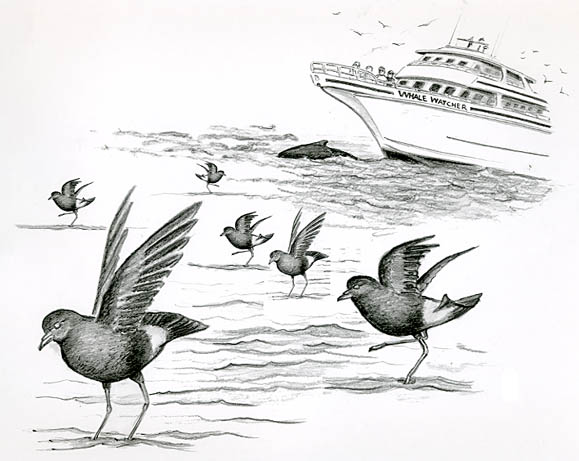

Anyone on a whale watching trip along the Atlantic coast is likely to see Wilson’s Storm-Petrels. (No relation to Woodrow Wilson or Strom Thurman) These abundant birds do indeed breed in the Southern Hemisphere, where they nest in countless millions on isolated islands that lay just off the coast of Antarctica. After a tough breeding season, and after dealing with the crazy Antarctic weather, the birds escape to the north to spend their summers with us and to entertain whale watchers who are tired of looking at those fat whales.

If you’ve ever seen a storm-petrel, I’m sure you would remember it. They have an unusual feeding style that makes them appear to be walking on water. With its wings spread, the bird tiptoes across the surface of the ocean while it looks for delicious plankton to eat. The name “petrel” is said to have derived from Peter, because according to Matthew, Saint Peter was able walk on water too. However, Matthew never made it clear if Saint Peter was also looking for delicious plankton.

It has been suggested that storm-petrels tiptoe on the water in order to stir up prey. In reality, their feet provide drag so the birds can hover in one spot without using the energy that flapping their wings would take. When feeding, the birds face into the wind and hang like kites, while their dangling legs provide the drag needed to keep them from blowing backwards.

One other interesting note about storm-petrels is their ability to smell. Very few birds have a sense of smell that is as well developed as a human’s is, but seabirds may be the exception. In the vast, featureless ocean there are no bird feeders for birds to look for. It is thought that seabirds, from miles away, are able to smell the oil that fish and krill give off as they are driven to the surface by other predators.

Anyone who would like to see these interesting birds had better like boats, because, with few exceptions, storm-petrels like to stay far out to sea. Even if you travel way down to their isolated nesting grounds you wouldn’t see them. The baby birds stay hidden in burrows all day and the parents only come ashore to feed them under cover of night. And if the moon happens to be too bright the parents might not even come at all, which forces the hungry young birds to send out for Chinese.

So there you have it, Doug. South American land birds typically don’t have a reverse migration, but some seabirds do. It’s another one of those things that makes bird watching so interesting, and confusing. Now that I have straightened out things with you, I have to go patch up things with my whale watching buddies. I know they are smart; guess I’ll find out if they have of sense of humor.