Dear Bird Folks,

A friend recently told me that city birds have to sing louder than country birds in order to be heard over the traffic and other sounds of urban life. What do you think?

– Beth, Brookline, MA

I think so, Beth,

Yes, birds do need to sing louder to be heard in urban areas. Take Brookline, for example. Your birds have to compete with the sounds of city buses and those screechy and antiquated Green Line trolley cars. And don’t forget the taiko drumming at Brookline’s annual Cherry Blossom Festival. Talk about loud. But I think the loudest night in the history of your city happened a few years back. On that night I was the featured speaker (and book signer) at the Brookline Booksmith. The bookstore was packed. By some estimates, nearly eight people had come to hear me speak. Then, at the end of my presentation, the crowd erupted in polite applause, applause that was so loud it could be heard in the cookbook section, nearly two aisles away. You should have been there. Hey, now that I think about it, maybe you were there. I remember seeing an attractive woman accompanied by an odd-looking man. Was that you? If it was, let me tell you something – you can do better than that guy. I’m just saying.

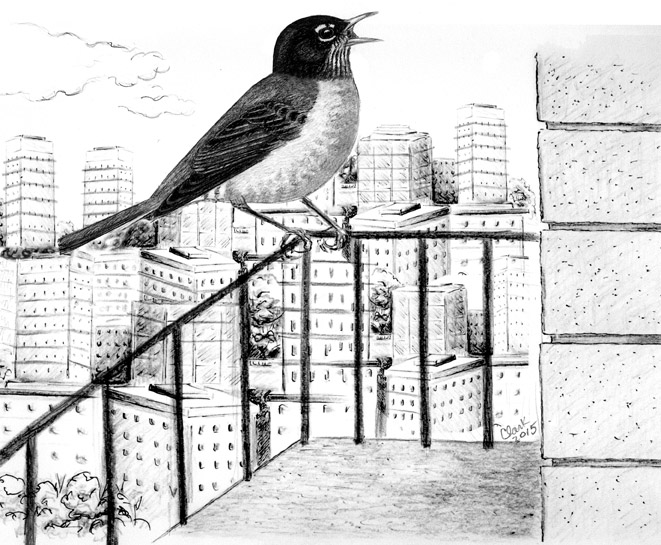

It amazes me how adaptable birds can be. Even in big cities where there is nothing but concrete, asphalt and pizza-stealing rats, certain species of birds have found a way to thrive. Instead of trees, the birds build their nests in the holes in traffic lights or behind advertising billboards. They have also changed their diet from eating healthy seeds to ingesting bits of nasty Pringles or feasting on the crumbs of overpriced gourmet cupcakes. The other thing birds struggle to do in the city is communicate. It’s critical for them to be heard in order to attract a mate and to ward off potential rivals. But with the hubbub created by the buses, subways and those eight people politely applauding for me, their little birdie voices can get lost. (BTW: This column marks the first time I’ve ever used the word “hubbub” in my life. I think it’s time I break down and buy a new thesaurus.) So, what do the birds do? Appropriately enough, a few of the younger birds have resorted to conversing via Twitter, but the less tech-savvy older birds have instead exhibited something known as the “Lombard effect,” in which they simply speak louder. It’s the same thing humans do in a restaurant with bad acoustics or a nightclub filled with loudmouthed drunks.

Not only do city birds have to crank their voices up a notch, but they also change their pitch or sing at higher frequencies. Why the higher pitch? Traffic rumbling tends to be at lower frequencies, so the higher pitch helps the birds’ singing stand out. It’s important to note that changes in songs aren’t restricted to the birds that are found in the concrete world of downtown. The “normal” birds of the ‘burbs are also affected. The Carolina Wrens that live in more energetic areas have a different song than the wrens that occupy more tranquil locations. Even changes to the natural landscape can affect birdsongs. As trees get cut down or fields become overgrown, the birds have to adapt. One clever researcher dug out some old recordings of White-throated Sparrows, which were made in the San Francisco area in the late 1960s, and played them for today’s millennium sparrows. The current sparrows showed far less interest in the older songs.

The results of this test suggest that as the environment changes the birds’ songs of the birds have also changed. The contemporary birds no longer consider the old songs worthwhile. This is a shame because a lot of good songs came out of San Francisco in the ‘60s. In an interesting study performed in Britain, researchers compared the songs of Great Tits. (Yes, Great Tits are real birds, so you don’t have to hide the newspaper from the kids.) They went out and recorded the songs of city tits and then drove out of town and played the recorded calls for the birds in the country. Typically, breeding birds respond aggressively when they hear songs from intruders. But in this case the reaction from the country birds was minimal. It was as if the city birds were speaking a different language…like someone from, say, Amherst, trying to understand someone from the Boston area (no offense).

In addition to changing their vocalizations, some birds have opted for a more proactive approach. Instead of fighting the sounds of the city, they often start singing after dark, when things have quieted down. In another British study (it seems the Brits are more obsessed with this topic than you are), they found that robins liked to sing late. (FYI: we are talking about their little weenie European robins, not our big American Robins.) With less traffic noise to deal with, the birds’ vocalizations can be heard over the din of anthropogenic ambient noise (aka, hubbub).

Yes, Beth, city birds do indeed change their singing habits in order to be heard. Their increased singing volume has made it possible for them to hear each other above all the urban racket. But what is interesting here is that the city/country birds might be headed towards a path of separation and perhaps two separate species. According to the British, there soon could be a distinct difference between city and country Great Tits…but I think we already knew that.