Dear Bird Folks,

While walking on Chatham’s Forest Beach today, I noticed these shorebirds. Would you mind looking at my photos and telling me what they are?

– Louise, Chatham, MA

I love photos,

Louise, I’ve mentioned this before, but the popularity of bird photography has made my job a zillion times easier. In the old days (about five years ago), folks would attempt to describe a strange bird to me and quite often these descriptions defied logic. I’d hear stuff such as, “The bird had one red wing and one blue wing, and a white head.” In the end I wasn’t sure if the person was looking at a bird or a flag or was suffering from an acid flashback. The rise of camera use has not only eliminated these whacky descriptions, but it makes identification more accurate. (And, if by some unlikely coincidence I’m not able to identify the bird, I can quickly forward the photo to a real birder for help…but let’s keep that a secret.)

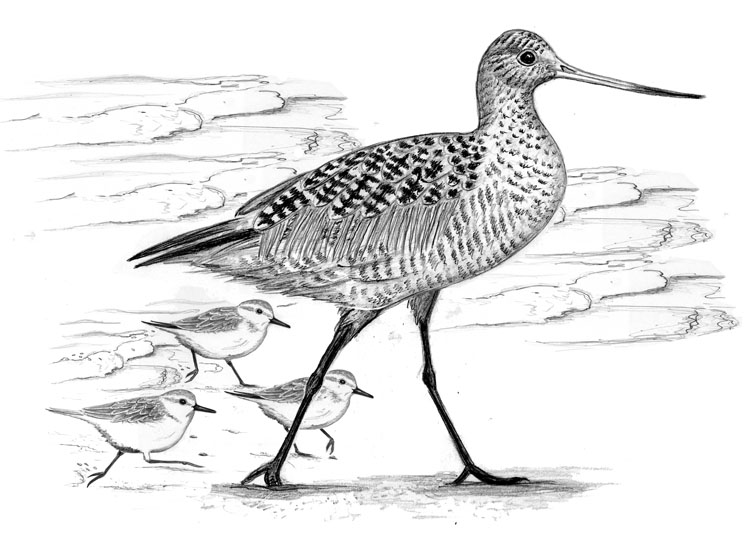

In your photograph there are two different species. The bird on the left is a Willet and the one on the right…isn’t. Got that? Everyone on Cape Cod should become familiar with Willets. They have quickly become the Cape’s most abundant breeding shorebird. But since I wrote about Willets last spring, I’m going to focus most of this column on the bird on the right, which is a Marbled Godwit. Believe it or not, Willets and godwits are both sandpipers, very large sandpipers. The word “sandpiper” fools a lot of my out-of-town customers. Their image of a sandpiper is the little bird we see running along the beach, playing tag with the waves. In fact, that energetic bird is a Sanderling (another species of sandpiper). Sandpipers come in all sizes, yet many of them don’t have the word “sandpiper” in their name (just to confuse the out-of-towners). Willets can be seen on Cape beaches spring, summer and fall, but Marbled Godwits only make brief appearances during their fall migration…and only if we’re lucky.

The first thing most people notice about godwits is their size. In the world of sandpipers, they are giants. Watching godwits feeding alongside tiny Sanderlings is almost laughable. It’s like watching preschoolers on the playground with NBA stars. In addition to their long legs, godwits have another super-long feature, their beaks. A godwit’s beak, which is half pink and half black, and slightly curved upward, is awkwardly long, looking as if the bird eats with a pair of built-in chopsticks.

Because godwits are shorebirds, you might assume they live and breed along the shore. But ironically this is not the case…unless you consider North Dakota to be a coastal community. During the breeding season, Marbled Godwits prefer to lay their eggs on western prairies and grasslands. Their nests are basically just shallow depressions in the ground and both sexes share the incubating chores. Using their natural coloring as camouflage, the nesting godwits are nearly impossible to spot. The birds are so convinced their cryptic coloring will hide them from predators that they rarely flush off the nest. During population studies, researchers have had to physically lift an adult off its nest in order to count the eggs. That’s what I call a stubborn bird…or maybe it’s just lazy.

When the breeding season is over, godwits leave the prairies and head for the coast where they finally act like proper shorebirds, digging into the mudflats with their long beaks. Along the Atlantic, small numbers of Marbled Godwits may be found from Virginia to Florida. However, the majority of them head for sunny California where they form huge flocks. On Cape Cod, we all go running out with our binoculars (and cameras) anytime a single Marbled Godwit is spotted. Yet, seeing a flock of several hundred of these big birds on the Left Coast isn’t unusual. I’m not sure why they like it out there so much, but apparently they don’t mind the traffic, mudslides and the pending earthquake.

Back to Willets for a second, Louise: Willets have earned their peculiar name by constantly yelling, “Will, will, willet. Will, will willet.” The origin of godwit isn’t nearly as clear. Some claim they hear “godwit” in the birds’ call, but I think that’s a stretch. Another theory states that godwit is a derivation of “good wit,” which means good bird…to eat. It seems back in jolly old England, Black-tailed godwits were considered to be the yummiest of all shorebirds and were routinely sought by hunters. Here in North America, their large size has made Marbled Godwits easy targets. Only help from conservation groups and governmental protection has kept them from going the way of Passenger Pigeons, Great Auks and iPhones 1, 2, 3, 4, 5…

On a different topic:

A few weeks ago I mentioned that people have been hearing mysterious bird sounds at night. I explained that the sounds were likely coming from tree frogs, probably spring peepers. I then heard from a reader who told me that he’s hearing a single click-sound during the day. He described it as the sound “ill-fitting dentures” make. A monotonous single note heard during the day is probably coming from our little pals, the chipmunks (hence the “chip” in chipmunk”). I wrote back to the guy and told him my thoughts. Although, I didn’t ask him how he happened to be so familiar with the sound of ill-fitting dentures…but I have a pretty good idea.