I finally got out:

With Labor Day well behind us, I decided it was safe to venture out once again. I wasn’t really confident about what I might find out in the real world, so I only went as far as the town of Wellfleet and Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary. I’ve written about this wonderful place before and wasn’t planning on doing it this time, but…

As usual, I arrived mid-week and very early in the morning. It was so early that there was not a single car in the parking lot or another person on any of the trails. I liked that. There were also no birds. I didn’t like that. There were no birds in the trees or in the tidal pools. Finally, I heard some distant crows that seemed to be agitated. I thought, so what? Crows are always agitated about something. I continued across the boardwalk and onto the mudflats. I was sure I’d at least see some migrating shorebirds here. I didn’t. There were no sandpipers, no herons, nor terns. I was just about to turn around and go back to bed, when I spotted a colony of Laughing Gulls, all huddled together behind a dune. Most of us are familiar with the Laughing Gull’s namesake raucous call, but these gulls were quiet. There wasn’t any laughter coming from any of them, not even a giggle. What the heck? Let’s review: There were no cars, no people and no birds in the trees. It was a little spooky. I half-expected to see Rod Serling come walking over the dunes. Instead of Rod, something else came over the dunes, and suddenly it all made sense.

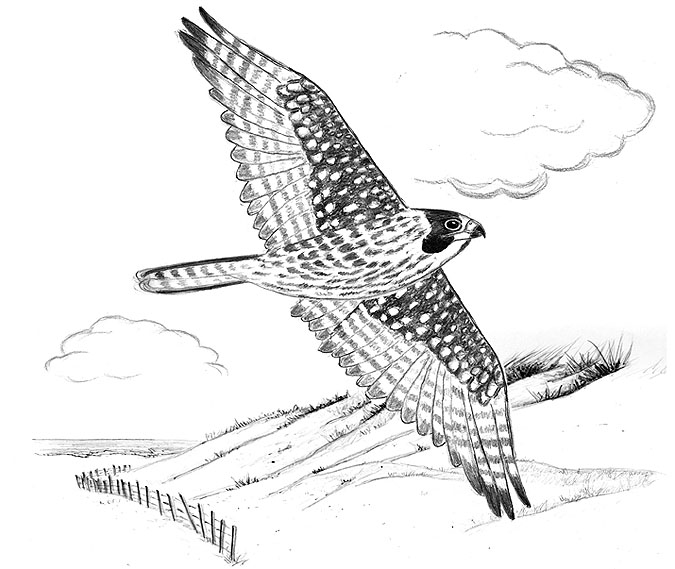

Blasting right into the middle of the gulls was a big, bad Peregrine Falcon. The gulls instantly took to the air, screaming as they went. I thought for sure I was about to witness a Laughing Gull laughing its last laugh, but they all got away. The falcon zipped down the beach, turned around and came right back at the gulls. But once again, they all survived. This was a young bird and it was either a lousy hunter or was just messing with the panicked gulls. (Young falcons are known to attack creatures they really aren’t interested in catching; it helps them sharpen their hunting skills.) After buzzing the gulls a few more times, the falcon turned inland, crossing the salt marsh with blazing speed, and disappeared. I didn’t know exactly where it went, but it must have taken a run at the crows I mentioned earlier because I heard them erupt in a deafening chorus of caws and hate. (Crows aren’t shy about voicing their displeasure upon seeing a predator, even a falcon.) Figuring the peregrine had moved on, I continued down the beach, only to have it zip past me seconds later. Man, this bird was fast.

Hearing the name Peregrine Falcon brings two things to mind: The bird’s mind-numbing speed (200 MPH in a dive), and its demise. In the 1940s, Massachusetts had fourteen very active falcon nests. These included one nest near the Quabbin Reservoir, where officials discovered that the birds had “inexplicably broken their own eggs.” This was unusual, but it didn’t set off any alarms…although it should have. A short seven years later, in 1955, we only had a single pair of falcons breeding in the whole state, and by 1966, there were none. They were all gone. And they weren’t just gone from Massachusetts or even New England; they were gone from the entire eastern half of the United States. Thanks a lot, DDT.

This was a dark time for falcons (and lots of other creatures, too). But then the ‘70s saw the banning of DDT and the signing of the Endangered Species Act. In addition, Cornell University created The Peregrine Fund, a non-profit dedicated to the protection and recovery of birds of prey, in particular these disappearing falcons. And happily, it all worked. By 1999, the falcon population had made a significant recovery and as a result, was ultimately removed from the Endangered Species list. How about that for good news?

We tend to think of falcons as birds of the wilderness, living on isolated mountaintops or in remote forests. While that certainly is true, it turns out that peregrines are far more flexible than some people thought. They can be found on any continent (that’s not Antarctica) and in any habitat. It doesn’t make much difference to them whether it’s hot, cold, wet, dry, high or low. They also don’t mind people or traffic. Here in Massachusetts falcons now nest in such diverse locations as on Mt. Sugarloaf in Deerfield and on the ledge of a condo in downtown New Bedford. Even our own Cape Cod Canal bridges have had falcon nests on them, with a Bourne Bridge nest having the most recent success. A few years ago, back when I actually traveled beyond Wellfleet, I spent an afternoon watching a peregrine chase pigeons from our high-rise hotel room in Boston. When my wife saw me pull binoculars out of my overnight bag, she started to question why I had brought them in the first place, but then just let it go. She’s used to it by now.

Fall is a good time to see Peregrine Falcons here on Cape Cod. Wanderers often spend time moving along our outer beaches. And even though the bird has become more common in recent years, it didn’t take the shine off my experience at Wellfleet Bay. Seeing a Peregrine Falcon soar over a sand dune is always a memorable event. Although if I had actually seen Rod Serling soaring over the dune, it would have been more memorable. But I’ll happily settle for the falcon.