Dear Bird Folks,

Could you please tell me what kind of bird this is?

– Betsy, Orleans, MA

Author explains:

Betsy came into my store this morning with a bird floating in a large glass bowl that was about the size of a punchbowl. The bird apparently had the misfortune of hitting Betsy’s window and then the double misfortune of landing in the liquid-filled punchbowl that was under her window. Since the bird was soaked, I had to dry it in the sun before I could indentify it. In the mean time I tried to figure out what the liquid was. At first I thought it was punch, thinking that perhaps the bird had sampled too much punch and that’s why it hit the window. But after I tasted the liquid, it turned out to be nothing more than plain old rainwater. How disappointing. I thought for sure I had just scored some free punch.

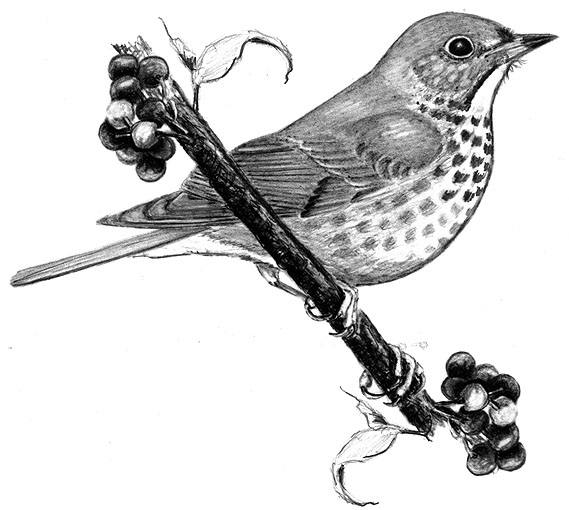

Once the sun had completed its drying job, I was able to tell that the unfortunate mystery bird was a Swainson’s Thrush. Thrushes, which include such notables as American Robins, bluebirds and Wood Thrushes, are some of the most recognizable birds in North America. However, Swainson’s Thrushes aren’t as easy as the others to identify. They are shy, woodland birds that are more often seen by serious birders and less often noticed by backyard bird watchers. And on the rare instance when a Swainson’s Thrush actually does visit a backyard, it is usually only for a quick drink at a birdbath or the occasional dip in a punchbowl.

Swainson’s Thrushes are slender birds with warm, olive-brown backs and speckled breasts. They have the posture of a robin, but without the potbelly. They also have a buff-colored ring around each eye, which helps us distinguish them from their similar-looking cousins. The thrush’s voice can also be used for identification. In the spring the males will sing their exquisite, haunting song, to alert the world to their presence. I know what you are thinking (actually, I have no idea what you are thinking, but I just need a way to tie these two sentences together): many thrushes also have exquisite, haunting songs. Yes, this bird’s song ascends up the scale, instead of downwards like all the others. The song starts off with a series of jumbled flute-like notes and then rises up, sounding echo-ish toward the end. Eventually, the song trails off and slips away like smoke carried by the wind. I realize that description is a little flowery, but that’s really how the bird sings. Really.

The Swainson’s Thrush is named after the nineteenth century English naturalist and illustrator, William Swainson. Swainson was a contemporary of many of the birding big shots of the time, including John James Audubon.

To my knowledge Swainson never even visited North America, yet his work must have been notable because several birds have been named in his honor. In addition to this thrush, there is the Swainson’s Hawk and the Swainson’s Warbler, plus a few others. As brilliant as Swainson was, his life wasn’t without controversy. In 1840 he did something that still has people scratching their heads. William Swainson left England, moved to New Zealand and married his housekeeper. This shocked everyone. I mean, if he already had a housekeeper what was the point of getting married? (Come on, ladies, it’s just a joke. Don’t send me letters.)

Swainson’s Thrushes do not nest on Cape Cod and are only seen here for a few weeks during migration. The vast majority of these sweet-singing birds breed in Canada, but each fall thousands of them fly over Massachusetts on their way to South America. Just don’t go running outside in hopes of seeing them. These birds like to migrate at night. The question that jumped into my mind when I first heard about thousands of thrushes flying overhead at night is how do we know? It’s dark at night, right? Well, believe it or not, some birders, with way better skills (and ears) than I have, are able to sit outside in the pitch black and “hear” birds as they wing their way south. How is this possible? Migrating Swainson’s Thrushes give distinctive, spring peeper-like “peep” call notes as they go. Researchers are somehow able to count the peeps and thus the number of birds. That’s amazing. I can’t even understand what British actors are saying on Downton Abbey, yet these folks can identify birds flying overhead in the dark. Very impressive.

Sadly, the Swainson’s Thrush that hit your window will not be the only bird to suffer such a fate this year. Annually, we lose millions of birds to windows. Glass is a huge problem, especially for young birds that have had no experience with man-made structures. While it’s impossible to protect all birds from all glass, there are steps we can take to save them from slamming into the windows in our homes. New ultraviolet window decals have been very helpful in stopping collisions. These decals, which are nearly invisible to our eyes, are warning beacons to birds. If window strikes continue to be a problem, Betsy, you may want to try some of these decals. The invention of ultraviolet decals has saved a lot of birds. Unfortunately, scientists still haven’t figured out away to keep birds from falling into punchbowls, but they’re working on it. Today, the windows…tomorrow, the punchbowls.