Dear Bird Folks,

A few weeks ago I read a story about how 2014 was the 100th anniversary of the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon. The story also mentioned another extinct bird, the Labrador Duck. I’m not familiar with this duck. What happened to it? Did the bird ever live around here?

– Lewis, Brockton, MA

That’s right, Lewis,

This year does mark the centennial anniversary of the extinction of North America’s most abundant bird. On September 1st, 1914, Martha, the last surviving Passenger Pigeon in the entire world, died all alone in the Cincinnati Zoo. At the beginning of the 19th century there were three to five billion (yes, billion) Passenger Pigeons flying free in the United States and Canada. By the end of the century they were all gone. While the reasons for their disappearance aren’t completely understood, land clearing and market hunting were certainly contributing factors. In addition, it has recently been discovered that many young Passenger Pigeons had taken up smoking, which is never a good thing.

The loss of so many Passenger Pigeons is mind boggling and inexcusable. But I think it’s equally astonishing that with all the environmental havoc we humans have created over the years, more birds haven’t followed Passenger Pigeons into oblivion. To be sure, bird populations are suffering, but at this point in the history of modern North American (north of Mexico), only three other bird species have officially been listed as extinct (not including subspecies and birds on the “maybe” list). There was the Great Auk, a bird that was flightless, so, of course, we killed them all. There was also the Carolina Parakeet (yup, we actually had our very own little parakeet), but we didn’t treat them very well either, and now they too are all gone. The last bird on this infamous list is the Labrador Duck. Labrador Ducks did indeed live around here, but their natural history is a bit cloudy. So don’t feel bad if you don’t know anything about them; nobody else does either.

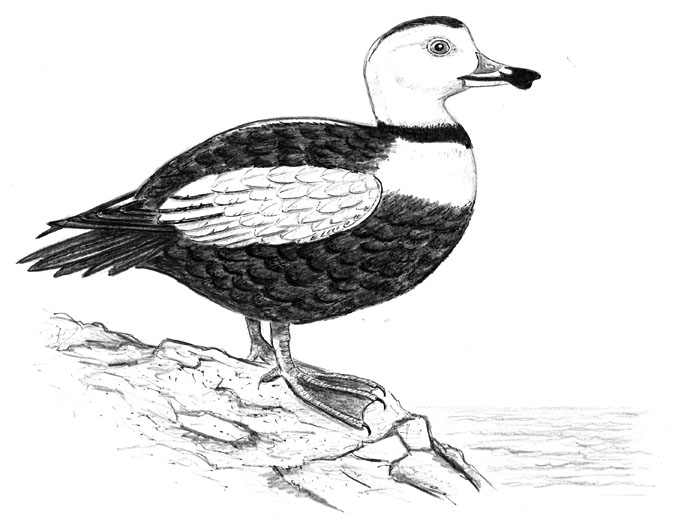

Labrador Ducks were beautiful eider-like black and white sea ducks. The ends of their bills were extra wide, which helped them feed on small clams and other such sea creatures. Labrador Ducks were still around during John James Audubon’s day and he even published a species account of them, complete with one of his famous colored illustrations. It’s interesting to note that the two birds Audubon used for his illustrations were shot by none other than Daniel Webster. Yes, the same Daniel Webster who was a prominent Massachusetts scholar and a U.S. senator (not the dictionary guy or a character on the TV series starring Emmanuel Lewis).

In the winter, Labrador Ducks were found along the New England coast. But in summer the ducks were on their breeding grounds, which was someplace, but no one knows where. One of the many pieces missing about the Labrador Duck’s natural history is where they laid their eggs. We simply don’t know. I’ve always assumed that Labrador Ducks came from Labrador (made perfect sense to me), but we don’t even know if that’s true. Today birders are armed with an assortment of notepads, binoculars and cameras to help them document their findings, but in the 1800s the only thing people were armed with were arms…firearms. Most folks shot birds to eat, not to study. Researchers have to rely on information provided by old hunters and that’s part of the problem. Many hunters, called the Labrador Duck the “pied” duck. However, they also called several species of ducks “pied,” including scoters and goldeneyes. So if hunters reported seeing a flock of pied ducks, we don’t know for sure which ducks they are referring to. It’s like when customers tell me they saw a “red bird” on their feeder. I don’t know if they saw a cardinal, a tanager or a bird with communist leanings.

The loss of the Labrador Ducks is such a mystery that one authority has proposed that the birds never even existed. It’s been theorized that what we call Labrador Ducks are actually hybrids produced when Steller’s Eiders and Common Eiders interbred. And since hybrids are typically sterile and don’t lay eggs, it explains why no one has ever found a Labrador Duck’s nest. Most other biologists argue that if the two eiders really interbred, why did they suddenly quit? Why don’t we see any more of these hybrids? Did the Steller’s Eider and the Common Eider have a falling out and abruptly stop finding each other attractive? I don’t think so. I mean, have you seen a Steller’s Eider? It’s one hot duck.

The last Labrador Duck was shot in 1875, and that was it. Why these birds all disappeared most likely had to do with the fact that they were always rare. Such a small population was not able to adjust to the pressures from market hunters and the changes we made to their feeding grounds (too many of their favorite clams ended up in our chowder). All of the Labrador Ducks quietly vanished before anyone even realized they were in trouble. Fortunately, Lewis, we now have laws that work to prevent the loss of rare species. The laws str too late to save the Labrador Ducks and Passenger Pigeons, but perhaps the list won’t get any longer if we all become a little less greedy, more environmentally responsible and above all else, convince young birds to steer clear of smoking. The bird on the White Owl cigar package is not really their friend.