Dear Birds Folks,

I know the Cape has Turkey Vultures, but do we also have Black Vultures? If so, how can I tell which is which?

– Allen, Orleans, MA

Swell timing, Allen,

It’s early December and other columnists are recounting stories of holiday cheer and family traditions, but instead you want me to write about creepy old vultures. Really? Can’t we save vultures for some more appropriate time of year, such as Halloween or Wall Street Week? Okay, I’ll do it, but next week I think I should write about a more cheery bird, like the beloved cardinal, just to make everyone else happy. Yup, that’s what I’ll do…maybe.

It was in the late 1970s when I took my first birding trip to Florida. Back then we couldn’t afford an airline ticket, so we had to drive. I picked my wife up right after school (she was a teacher, not a student, so don’t start any rumors) and we drove all through the night. Our first stop was at Florida’s I-95 Welcome Center. Two things impressed me about that stop. First: They gave us free orange juice. Free juice! (In a Massachusetts rest area you are lucky to get toilet paper.) I also remember seeing lots of vultures. The sky was filled with them. In the ‘70s vultures were a rare sight on Cape Cod, but in Florida they were everywhere. This is when I began to understand why so many Northerners travel to Florida. They simply want to see more vultures and get free juice…and who can blame them?

A lot of people don’t like vultures and it’s probably due to the birds’ habit of eating dead things. But when you think about it, we all eat dead things, especially if there’s barbecue sauce involved. The difference is our meat comes all wrapped up, with cute names such as brisket, sirloin or bottom round. (Heck, I don’t even eat meat, yet I’m interested anytime I hear the words “bottom round.”) Vultures aren’t nearly as fussy as we are. They eat meat wherever they find it, especially if it’s still attached to the original animal. If we see a vulture on the side of the road, chowing on a squashed rabbit, we think “gross.” But if we see a guy in a restaurant eating prime rib, we think “yum” (or at least some people think that).

As I mentioned, vultures are fairly new around here. The Commonwealth’s first Turkey Vulture nest wasn’t discovered until 1954. It was found in the Berkshire town of Tyringham (yes, it’s a real town) and ever since our Turkey Vulture population has been expanding. But this hasn’t been the case for their cousins, the Black Vultures. For the most part, they have remained in the South, making only rare cameos this far north. But then, in 1998, an adventurous Black Vulture couple decided to build a nest in the Blue Hills Reservation in the town of Milton (yes, it’s a real town). Since then, they too have begun moving into Massachusetts, but at a much slower pace than the far more common Turkey Vultures. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t double check whenever you see one. If I were you, Allen, I would learn how to tell the two birds apart. Wait! I’m supposed to teach you that. I almost forgot.

The key to identifying our two vultures is noticing their heads. Turkey Vultures have naked, ugly bright red heads, much like Wild Turkeys have, hence their name. The heads of Black Vultures are also naked and probably just as ugly, but since their heads are gray, and not bright red, they don’t look as scary. Black Vultures are all black, looking like giant crows, with gray heads. Turkey Vultures also appear to be black, but if you look closely you’ll see their feathers are more brownish, looking like giant muddy crows.

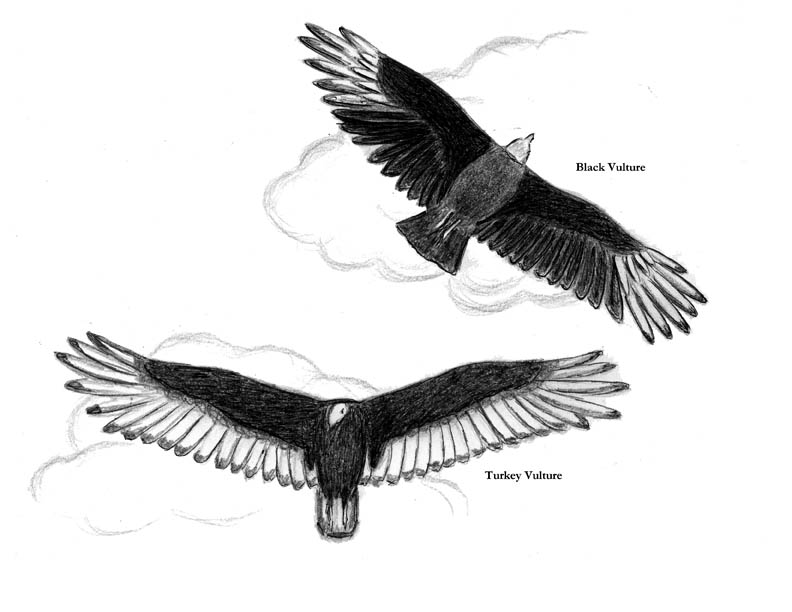

Turkey Vultures are noted for soaring with their wings held in a steep dihedral (V-shape). They also tend to glide unsteadily, rocking from side to side, flying as if they just left a pub. The dihedral of a Black Vulture is less pronounced and more hawk-like. A few years ago, Cathy (the artist who draws the illustrations each week) tested a pair of binoculars that contained a built-in camera. One of her test shots was of a passing Turkey Vulture, or at least she thought it was. After I took a look at the photo, I was thrilled to see it was a Black Vulture. How could I tell? When seen from underneath, a Black Vulture’s wings are all black, except near the tips where the “hands” are light colored. Conversely, the undersides of a Turkey Vulture’s wings are half black and half white (black in the front and lighter in the back and on the ends). Noting these contrasting wing colors is the easiest way to separate the two vultures in flight. In other words, if the wings of your vulture look like black and white cookies, it’s a Turkey Vulture. But if it has jazz hands, it’s a Black Vulture. Most field guides don’t describe the birds this way, but they should.

Identifying the differences between our two vultures is a good thing to know, Allen, as both birds are becoming more common. Although, at this point, 99% of the vultures we see on the Cape will be of the turkey persuasion. Nevertheless, it doesn’t hurt to give each vulture you see a careful evaluation. And by the way, that pair of binoculars with the built-in camera wasn’t very good so don’t get any. That gives me an idea; next week I’ll write a column about choosing binoculars. Folks might find it helpful, especially in light of the upcoming gift-giving season. I know I promised to write about cardinals, but I think we all knew that wasn’t going to happen.