Dear Bird Folks,

I understand that some of the robins we see around here in the winter have actually migrated down from Canada. Is there a way to identify the Canadian robins from our summer robins?

– Robert, Bourne, MA

Not me, Robert,

The stereotypical answer to your question is that it’s easy to identify Canadian robins. They are the birds that say, “Tweet, eh” and smell like Tim Hortons donuts. I’m not going to do that. I don’t want to be accused of profiling. But wouldn’t it be cool if Canadian robins really did smell like donuts? Donuts have the best smell ever. (Sorry, bacon and coffee, but it’s true.) Instead, I’m going to tell you what most people think Canadian robins look like, but not until I have a snack first. Suddenly, I feel like eating a donut or two.

Many backyard bird watchers swear that the robins we see in the winter are larger than the summer robins. Every December someone tells me, “I’m getting a lot of fat robins in my yard. They must be the ones from Canada.” This isn’t really true. Summer robins and winter robins (often from Canada) are about the same size. Although I can totally understand why people think winter robins are fat. But the fact is all robins are fat, all the time. That’s just how they roll. No matter which country they come from, robins have a potbelly, like a guy who has spent too much time at Tim Hortons. Also, all birds tend to fluff out a bit more in the winter, so they may look slightly plumper, but it doesn’t mean they’re from Canada. It just means it’s cold outside. Here’s how to tell if you are seeing Canadian robins…maybe.

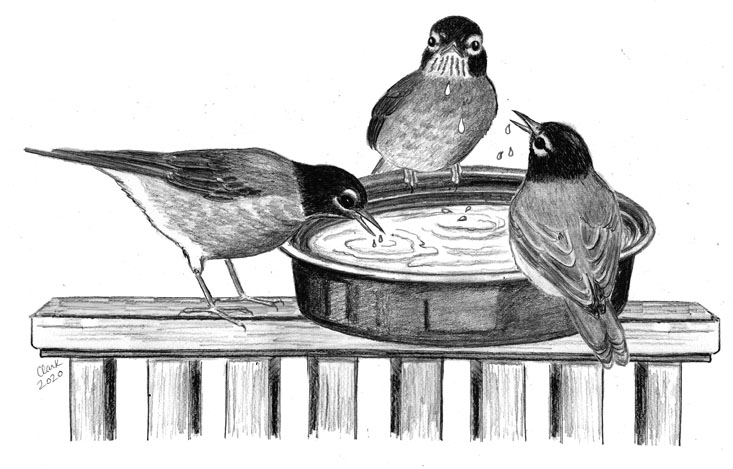

A few winters ago, my wife was working at the kitchen table when she noticed several robins drinking water out of “her birdbath,” which is actually an old black plastic dish that once contained leftover lasagna. (Meanwhile, on the other side of the house, my fancy heated birdbath was getting zero activity and I wasn’t happy about it.) My wife told me that some of the robins were darker than the others. I explained that it’s a male/female thing. The female American Robins are slightly more washed out than their male counterparts. She disagreed, telling me that some males were darker than other males. Determined to prove her wrong, I decided to sit and watch the lasagna birdbath for a while. Within minutes a flock of robins flew in to get a drink, and one of them was indeed darker than the rest. My wife was right. Grrr. She not only had a better birdbath than I had, but now she knew more about birds, and I wasn’t happy about it.

Was this darker robin from Canada? That’s a good question and not one with a clear answer. There are seven subspecies of American Robins, each with its own plumage variations. Birds from dryer, western locations tend to be lighter in color; robins from northern coastal regions, where conditions are more humid (like Atlantic Canada), are darker. What does a darker robin look like? This sounds like an easy question, but the differences are slight. We think of this bird as being “robin redbreast,” but in reality the breast is more orange, or rufous, on the male. And if you look closely, you’ll see the breast also has a fair amount of white mixed in, like the hair on the head of a middle-aged man. There is also a white patch (with black streaks) on the throat. The back is gray, while the head is mostly black. The so-called darker birds have very little white showing on their breast and throat, and the black on the head flows down onto the back. Got all that? To make things even more confusing, within a geographical area there can be plumage variations. These variations are subtle and often go unnoticed, unless you happen to be an expert…or my wife.

A hundred years ago none of this was an issue, since robins were far less common around here in the winter. (Remember when we all thought robins were a sign of spring?) Things have been changing in recent decades, however. It appears that more and more robins are doing less migrating and are spending the winter closer to their summer breeding grounds. And the birds that do migrate aren’t traveling as far south as they once did. What is the reason for this lack of migration? The kneejerk reaction would be to point a finger at climate change, and that would not be wrong. Milder temperatures and less snow cover have certainly made the winters more hospitable for the birds, and for us as well.

In addition, our landscaping and agricultural habits have also benefited the birds. The old adage tells us that the early bird gets the worm, but in the winter there are no worms to be gotten, no matter how early the bird gets up. Instead, winter robins switch their dietary habits and become fruitarians. They substitute our ornamental crabapples, cherries, holly and juniper berries for bugs and worms. Makes sense to me.

I wish I knew of an easy way to identify our resident robins from the birds that have flown down from Canada, Robert. Size isn’t really a good indicator and while Atlantic Canada does produce darker birds, that’s not a perfect method either. It would be nice if the Canadian birds really did smell like Tim Hortons donuts, but alas, they don’t. However, if you find a bird that smells like lasagna, it’s not from Canada or even Italy, but almost certainly from my wife’s birdbath.