Dear Bird Folks,

The other night (in mid-January) I heard two owls calling outside my house and each owl gave a distinctly different call. One owl’s hoots were deeper than the other one. I’d say their pitch was about a major third apart. (I used to be a music teacher.) The two owls continued for about thirty minutes, or until I fell asleep. The question is: What was all the hooting about and do you think these were two different species of owls?

– Joe, Brewster (MA)

Very comprehensive, Joe,

The rest of the readers don’t know it (because I did a lot of editing of your question), but your description of the owl calls was one of the most complete accounts I’ve ever received. Beyond the calls being “about a major third apart” (whatever that means), you included the exact number of hoots each bird gave. Also, you described the length of time between hoots, the intensity of the hoots and whether the owls were talking with their mouths full or not. That’s very impressive. It’s too bad you didn’t need to bother going through all that trouble, because I’m wicked smart. I knew the answer to your question as soon as I read your opening sentence. Okay, fine. The truth is Brewster only has one species of owl that hoots. It’s that simple. However, if you want to believe that I’m wicked smart, don’t let me stop you.

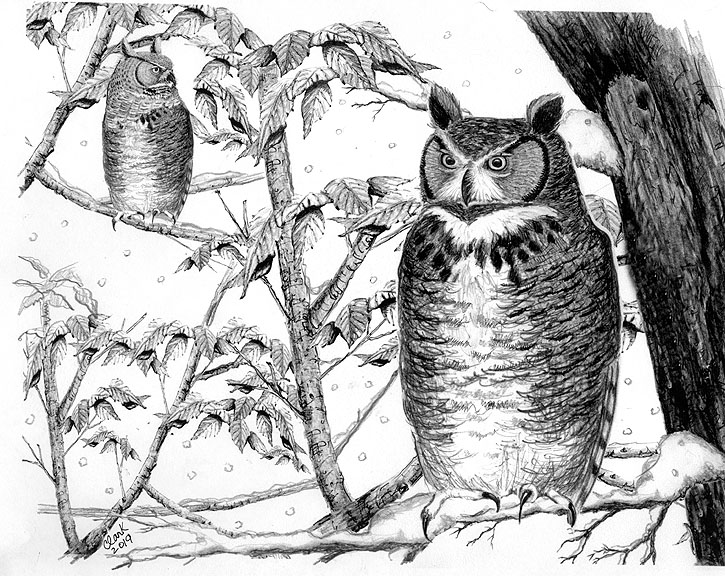

The calls you heard were not coming from two different species of owls, but from a breeding pair of Great Horned Owls. Yes, breeding owls in January. Most other birds couldn’t imagine breeding this time of year, but great-horn couples like to get busy early. For sure, Great Horned Owls can be heard calling any time of year, but they really crank things up in the middle of winter. Why now? As is the case with all breeding birds, it’s about food supply. Songbirds nest in the spring when the nutritious insects become available. But Great Horned Owls hate spring (and probably insects, too). Their babies need meat and lots of it. Hunting is easier before the burgeoning spring foliage can provide cover and protection for the owls’ prey. And great-horns have a long list of prey. These ferocious predators will hunt and eat just about anything that moves, including mice, rabbits, squirrels, skunks, opossums, house cats, and any children who don’t listen to their parents.

So, what’s with all the hooting? Great-horned Owls normally remain together for life, so they use hooting to help solidify their pair-bond. It’s way cheaper than buying flowers, jewelry or skimpy things from Victoria’s Secret (although not nearly as fun). The hooting also lets the other owls in town know that this particular territory is occupied. Humans put up fences, walls and signs that say, “Beware of dog” to mark their territories, but owls can’t be bothered with all that ugliness, so they hoot.

Like most owls, great-horns have a variety of vocalizations. Their sounds range from customary hooting, to squawks, screeches, screams, bill snapping and an assortment of other random noises. But when a couple wants to announce its territory, their calls become purposeful and synchronized. The female usually starts the conversation (no surprise there) with a series of six or seven hoots and then waits for the male to reply. After about thirty seconds the male calls back with five hoots of his own. Even though he is smaller than his mate, his calls are lower pitched (or as some people say, “about a major third apart”). This duet may last for nearly an hour. As things progress, the pair becomes increasingly stimulated and this results in shorter intervals between responses. It finally reaches a point where the male doesn’t even wait for the female to finish hooting before he starts his reply. The two birds are now hooting at the same time without even listening to what the other is saying…just like most married couples.

These nightly duets may go on for several weeks, but once the first egg is laid, the birds tend to quiet down and focus on raising a family. Female great-horns are excellent mothers and can keep her eggs nice and warm, even when the outside temperature falls well below zero. That’s right, when it’s below zero outside Mrs. Owl’s eggs are still cozy in her nest. Well, it’s not really “her nest.” You see owls don’t build their own nests. They “borrow” readymade nests from other large bird species, such as Red-tailed Hawks, ravens and crows. Some people might say that owls are lazy because they don’t build their own nests, but I totally understand. Owls are nocturnal. It’s hard enough for them to find food at night, but constructing a nest after dark would be super hard. Can you imagine what a nest made in total darkness would look like? It would probably look like I made it.

Once Great Horned Owls establish a territory, Joe, they tend to remain there year-round. If you heard them calling once, there’s a good chance you will hear them again. But if for some reason you don’t hear them anymore, it doesn’t mean they have left your area. Most Great Horned Owl duets tend to happen well after midnight, a time when you are likely sound asleep, with visions of sugarplums and major thirds dancing in your head.