Dear Bird Folks,

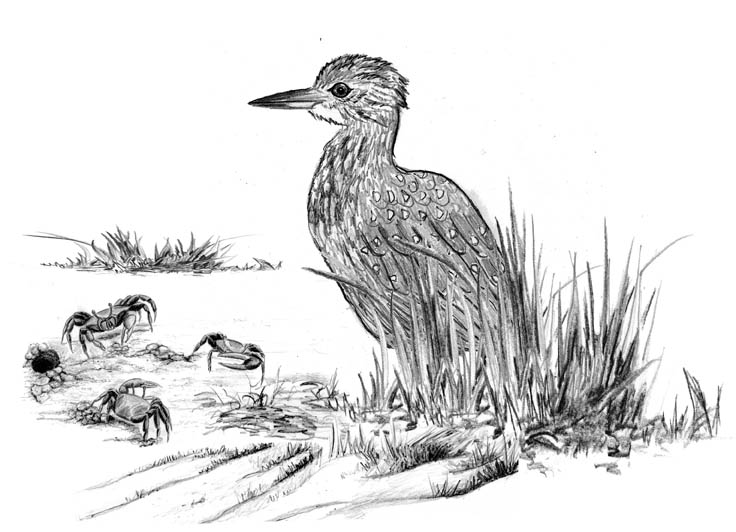

This photo was taken in the marsh, off the bike trail behind Eastham’s Coast Guard Beach. It looks bittern-ish to me. What do you think?

– Amy, N. Eastham, MA

Yes, it is, Amy,

The bird in your photo is indeed “bittern-ish,” but it’s not actually a bittern. It’s a Yellow-crowned Night-Heron. Bitterns and night-herons have a lot in common: They are both large, long-legged wading birds, with extended beaks, and both earn their living by hunting fish, crabs, frogs and other such creatures in the area marshes and wetlands. In fact, one of the few things they don’t have in common is their appearance. They don’t look at all alike…except sometimes they do. Now do you understand?

In order to remain undetected while searching for prey in cattails and reeds, American Bitterns are cryptically colored. They are basically brown birds with brown streaks, kind of like giant sparrows. They’re not much to look at and that’s the way they like it. They are solitary birds, spending their days foraging and trying to avoid detection…and each other. Bitterns could easily be on a poster for social distancing. By contrast, the plumage of the Yellow-crowned Night-Heron is far more distinctive. They have handsome gray bodies, with black heads, white cheek patches and their namesake yellow (cream-colored) crowns and head plumes. Confusing an adult night-heron with a bittern would be like confusing a cardinal with a grackle; the two birds look vastly different. But here’s the thing: young night-herons do not have the same handsome coloring of their parents. They are streaky brown for the first months of their lives and indeed look much like bitterns…or look bittern-ish, as some people in N. Eastham like to say.

Yellow-crowned Night-Herons are southern birds, with only a few, if any breeding this far north in Massachusetts. As their name indicates, night-herons feed at night, but can be seen foraging during the day as well. The key factor is not so much the time of day, but the height of the tide. Most other herons will eat fish, worms, snakes or whatever happens to come their way, but yellow-crowns are like the folks in Maryland…they really love their crabs. As a result, yellow-crowns schedule their hunting trips for a few hours before or after high tide, when crab fishing is the best, even if the best tide is at night. They also aren’t fussy about which crabs they eat. The list includes fiddler crabs, blue crabs, green crabs, stone crabs and toad crabs (toad crabs?). Some yellow-crowns breed farther inland, where they are forced to give up their crab diet and instead seek out crayfish, which are like little lobsters, but much cheaper.

Our other egrets and herons (except for the reclusive bitterns) tend to be stately birds, often seen standing tall in marshes or along the water’s edge. But the same thing can’t be said for night-herons. Instead of standing tall, they are often hunched over and have a stubby Danny DeVito look about them. This is particularly true for their more abundant cousins, the Black-crowned Night-Heron. One of the better places to see either species is at Hemenway Landing* in Eastham, especially on a summer’s evening. Right around sunset, both night-herons will leave the nearby roost to venture into Nauset Marsh in search of their dinner. The poor light doesn’t allow for great looks, but it’s still pretty cool to watch their silhouettes move across the evening sky. And you don’t have to worry about the birds sneaking past you in the dark either. They readily announce their presence with a characteristic “kwonk” as they leave their roost. It’s a little spooky.

*Although I’m not totally certain, I’ve always assumed that Hemenway Landing was named in honor of Harriet Hemenway, the driving force behind the creation of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. Thus, it’s Hemenway Landing, not “Hemmingway” as many folks mistakenly call it. The landing wasn’t named after Ernest Hemmingway. This is yet another example of how society blindly gives credit to men, instead of the women who deserve it. (My wife made me add that last sentence.)

Have you ever been to Bermuda, Amy? If you have, then you know that Bermuda is noted for several things, including: beautiful beaches, ugly shorts, terrifying mopeds, smelly onions and, of course, triangles. And also, land crabs, lots and lots of land crabs, which were a problem. Crab burrows destroyed lawns, especially on golf courses. The crabs themselves were a pain for gardeners, because they ate their plants. (Who knew?) As usual, poison was the go-to method of controlling the crabs, but then ornithologist David Wingate had a better idea. While he was doing fieldwork, Dr. David discovered the fossilized bones of a night-heron. David theorized that if night-herons were reintroduced, in particular, Yellow-crowned Night-Herons, they might help control the excessive crab population. In the 1970s, David’s team brought in several young night-herons (you know, the ones that look bittern-ish) from Florida and the project worked. Today, Bermuda has a lot more night-herons and a lot fewer crabs, and no need to use poison.

Yellow-crowns are rare on the Cape, Amy. When we do see one, it’s often a young bird, because the kids tend to wander far away after they leave their nest…unlike human kids, whose idea of wandering is to the nearest basement. Maybe our kids are turning into bitterns. Someone should look into that.