Dear Bird Folks,

The birds on my feeder have been looking a little bedraggled lately. Do you think it’s because of the long hot summer we’ve just gone through? Will they ever recover?

– Ellie, Sandwich, MA

No, Ellie,

The birds aren’t bedraggled from the long, hot summer; you must be thinking of me. Between the heat, the traffic and everything else, I start to look rather worn out at this time of year. Some people will argue that I looked that way even before summer started, and they may be right, but I’m definitely worse now. Birds, on the other hand, look their absolute best in the spring. The hard work of raising a family eventually takes a toll on their feathers, but that’s not the main reason why they are looking so scruffy. Just about every bird, whether they’re on your feeder or not, is in the middle of their annual molt. Late summer is when birds ditch their old outfits in favor of brand new ones. They may appear a little rough for a few weeks, but once the new feathers have grown in, they’ll be as good as new. (It’s just too bad the same thing can’t be said about me.)

“Light as a feather” is not just a hackneyed expression; it’s an actual fact. Feathers are strong, durable and amazingly light. They also perform a whole host of critical functions. They keep birds warm on cold nights and dry when it’s raining. Feathers also have a lovely esthetic quality, which helps draw the attention of possible mates…and nerdy bird watchers. Most importantly, feathers enable birds to fly. Without properly maintained feathers, birds would be cold, wet and ugly, and have to travel by bus. Thus, birds can’t afford to take their feathers for granted…and they don’t. Much time is spent each day grooming and primping, but ultimately no amount of maintenance is going to keep their feathers functioning forever. Wear and tear from diving into water, flying through dense trees or running in thick grass takes a toll. The time comes when their feathers have to be replaced, and that time is now (which is September, in case you’ve misplaced your calendar).

Many birds have two distinct plumages. They have a breeding and a non-breeding plumage, and that’s it. Ornithologists, however, thought this was way too simple and decided to make things confusing, as only ornithologists can. They added more plumage labels, such as basic, pre-basic, alternative, pre-alternative and partial pre-alternative plumage, and I wish I were kidding. Regardless of what terms we use, birds typically molt this time of year because they simply have free time on their schedule. The breeding season is over, their kids have come and gone and now the adults are able to have some “me” time. Late summer also offers an abundance of natural food, which is important since growing new feathers takes a fair amount of extra energy. Plus, with the breeding season over, the birds don’t mind if they look a bit ratty. (Only bird watchers care what birds look like now, and we don’t count.)

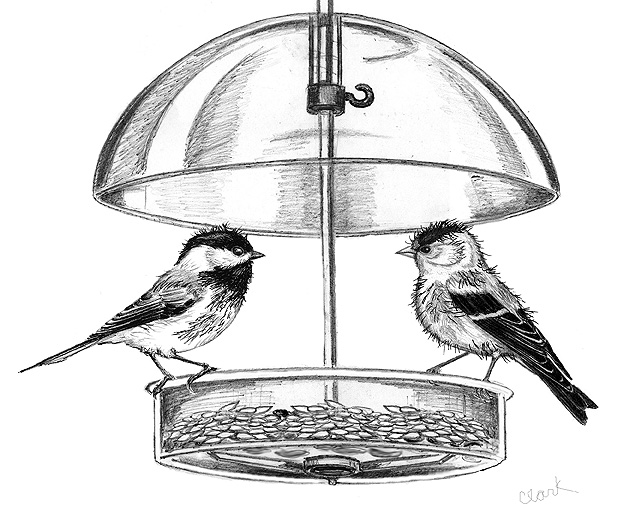

Like many aspects in the bird world, molting is complicated and varies widely amoong species. Some species molt annually, while others have partial molts twice or even three times a year. Some emerge totally different after their molt and others don’t. Chickadees look exactly the same before and after they’ve completed molting, but when the male goldfinch has finished his fall molt, he looks like a different bird… and a different gender. Some birds take molting in stride and continue with their daily activities as if nothing different is going on. But Gray Catbirds, at least the ones in my yard, hate being seen with their hair in curlers, and tend to disappear into the thickets until they look good again. Other birds, particularly cardinals and Blue Jays, probably should spend more time in the thickets, since they often lose their head feathers so quickly that they will actually become bald, which causes my phone to ring, and ring, and ring. And, yes, their head feathers will grow back, and no, their heads won’t get sunburned. Don’t bother putting out tiny hats or sunscreen; your birds won’t use them.

Bald heads aside, molting is a gradual process and it needs to be. If birds lose too many feathers too quickly, their ability to fly will be compromised. Ducks are an exception to this rule. They actually lose all their flight feathers at once and for a nearly a month they are earthbound, or more accurately, water-bound. Fortunately, ducks are able to use the relative safety of water for protection. While they are waiting for their feathers to grow back, dabbling ducks such as Mallards and Wood Ducks spend their days hiding in dense thickets along the edges of quiet ponds and wetlands. Conversely, diving ducks move to larger and deeper bodies of water, where they can dive below the surface to escape danger. (Although I really think they dive because they don’t want anyone to see them looking that way.)

Birds aren’t real pretty right now, Ellie, but in a few weeks they’ll be sporting their brand new non-breeding plumage. Or is it their basic, or pre-basic, or alternative, or pre-alternative and or partial pre-alternative plumage? If anyone can figure it out, let me know. On second thought, don’t bother. Just writing it makes my head hurt.