It’s after Labor Day:

There once was a time when Labor Day meant vacationers headed home and kids went back to school, but COVID has made things a little less certain than they used to be. Regardless, I just found out that one thing is certain: the newspaper has an early holiday deadline. Being short on time, I’ve decided to combine a few past columns that were basically written about Ospreys, when they leave and where they go. I’m sure most folks won’t remember reading any of this before, but if for some reason it does look familiar, just assume you dreamed it and move on.

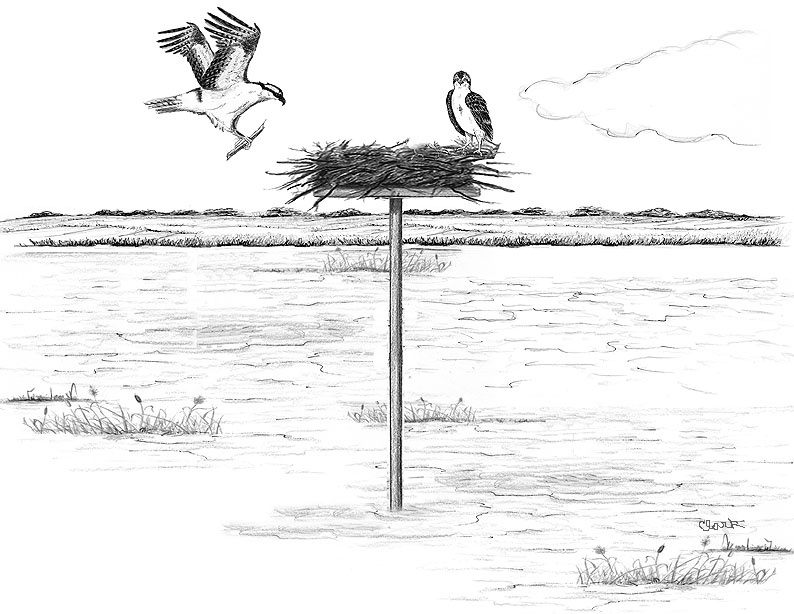

We all get excited in the spring if robins build their nests in the bushes near our kitchen windows. But that show doesn’t last long. In a few short weeks the eggs hatch, the babies grow feathers and leave the nest, and never return. If you blink, you’ll miss the whole event. But with Ospreys you can blink all you want, and even take a nap, because their breeding cycle is way longer than a few weeks – it’s more like five months. Adult Ospreys return to New England in March and after some fancy courting and minor nest repairs, they get down to business. The female will lay two or three eggs and then, along with her mate, spend the next five to six weeks incubating those eggs. What a boring job that must be for the adults; they have to sit and do nothing for hours on end. Fortunately, their nests are high above the ground, so at least they have a nice view. How’d you like to be an incubating bluebird? They have to stare at the dark walls of a birdhouse 24/7. And what about the robins nesting near a kitchen window? They’re stuck looking at dirty dishes piled up in the sink all day. No wonder they finish nesting so quickly.

After six weeks of incubation, the baby Ospreys finally crawl out of their shells, but they’ll need another two months of constant feeding and attention from their parents before they’ll become strong enough to fly. But even flying babies aren’t capable of fending for themselves. They still need to have food brought to them. Fledged Ospreys are much like human toddlers, as neither can make their own meals. At two years old, most children are able to walk and download stuff on the computer, but it will be a while before they acquire the skills needed to make their first PB&J.

Even after taking their initial flights, the young birds still follow the adults around and beg to be fed. Eventually, the kids decide that all this silly begging makes them look bad in front of their friends and they start catching fish on their own. Most other birds of prey are taught how to hunt by their parents, but that doesn’t happen with young Ospreys. There are no fishing lessons given by the adults or instruction manuals for the kids to read. They just wake up one day and suddenly they can catch fish. It comes to them naturally…much like a two year-old toddler who innately knows that the best sandwich is a PB&J.

By late August it’s time for the adults to head south. The female leaves first. After months of tending nagging babies she’s had enough. (Last week a lady told me that she could tell the female Osprey from the male. When I asked her how she could tell, she responded by saying, “The female looks exhausted.” I didn’t argue.) The male stays behind to keep an eye on things for a while, but ultimately he can’t take it anymore either, and also moves out. At this point the young Osprey are on their own and they aren’t happy about it. They call and whine, hoping that someone or something shows up with free food, but they only manage to attract concerned humans who hear the begging and think that something is wrong. It isn’t.

As August turns into September, the young birds get restless and also feel the urge to head south, although they don’t all leave at the same time. Osprey migration is not a family event. The birds don’t all pile into a minivan and head down I-95, singing songs and playing “I spy with my little eye” (which is too bad for them because it’s a fun game). Each Osprey nestling leaves when it’s ready. For the most part, that means the older and stronger birds head out first. The younger siblings may stay back for a few more days to build up their strength…and courage. Eventually, they too make the leap of faith and take the long, scary flight to the wintering grounds alone. Where are these wintering grounds? Studies have shown that most New England-born Ospreys spend the winter along the coast of northern South America. Here a young bird will remain for two years, only returning to our area again in time for its second birthday party and to have its very first PB&J…maybe.

On a different topic:

The mysterious bird illness that caused so much hand-wringing back in July turned out to be a false alarm. Mass Audubon now claims that we are all free to put our feeders and birdbaths back outside (as long as we promise to keep them clean and well maintained).

Finally:

I would like to conclude this column with my annual end of the summer cautionary statement about meal moths. Meal moths are harmless but annoying insects that love all cereal and grain, including birdseed. The hot days of July, August and even September are their prime breeding months. Birdseed should be used up quickly this time of year and not stored in the house, or you might end up with very tiny flying houseguests that will stay with you well beyond Labor Day, and I’m not kidding.